Vive L’Amour

In the films of Tsai Ming-liang, as in much of the so-called slow cinema, a single shot is just as likely to be worthy for discussion as an entire scene. In fact, a single shot often is an entire scene. So why not begin a piece on Vive L’Amour, Tsai’s second full-length feature currently on rerelease to coincide with a long-overdue restoration, by considering its opening two shots.

In the first, a key left in an apartment door dangles tantalizingly in the foreground while a young man makes a delivery in the background. After some trepidation at the elevator doors, he snatches the key on his way out. In the second shot, the camera fixes on the security mirror of a convenience store as the same man wanders about. He leisurely picks up a water bottle, takes a few paces towards us and uneasily raises his puppy-dog eyes straight at the camera. For a panicked moment we feel like we’ve been caught in the act of watching, that is until the man starts fixing his hair with his hands. False alarm — he’s just checking himself in the mirror.

This momentary suggestion of a crack in the fourth wall makes for an unusual and slyly amusing opening to a film concerned with what people are like when they’re alone. And I mean really alone — unseen by other characters, but also conveying the sense of being genuinely unwatched by any viewer on the other side of the screen. Or at least, that feels like it’s the case when our protagonist, Hsiao-kang (the ever-wonderful Lee Kang-sheng, who has appeared in all of Tsai’s films) slips in, unnoticed, to the vacant luxury apartment he stole the key to. He leisurely strips off, gets in the jacuzzi, and submerges himself in the water. Sometime later, he makes his way to the bedroom, takes out a Swiss army knife and slits his wrists.

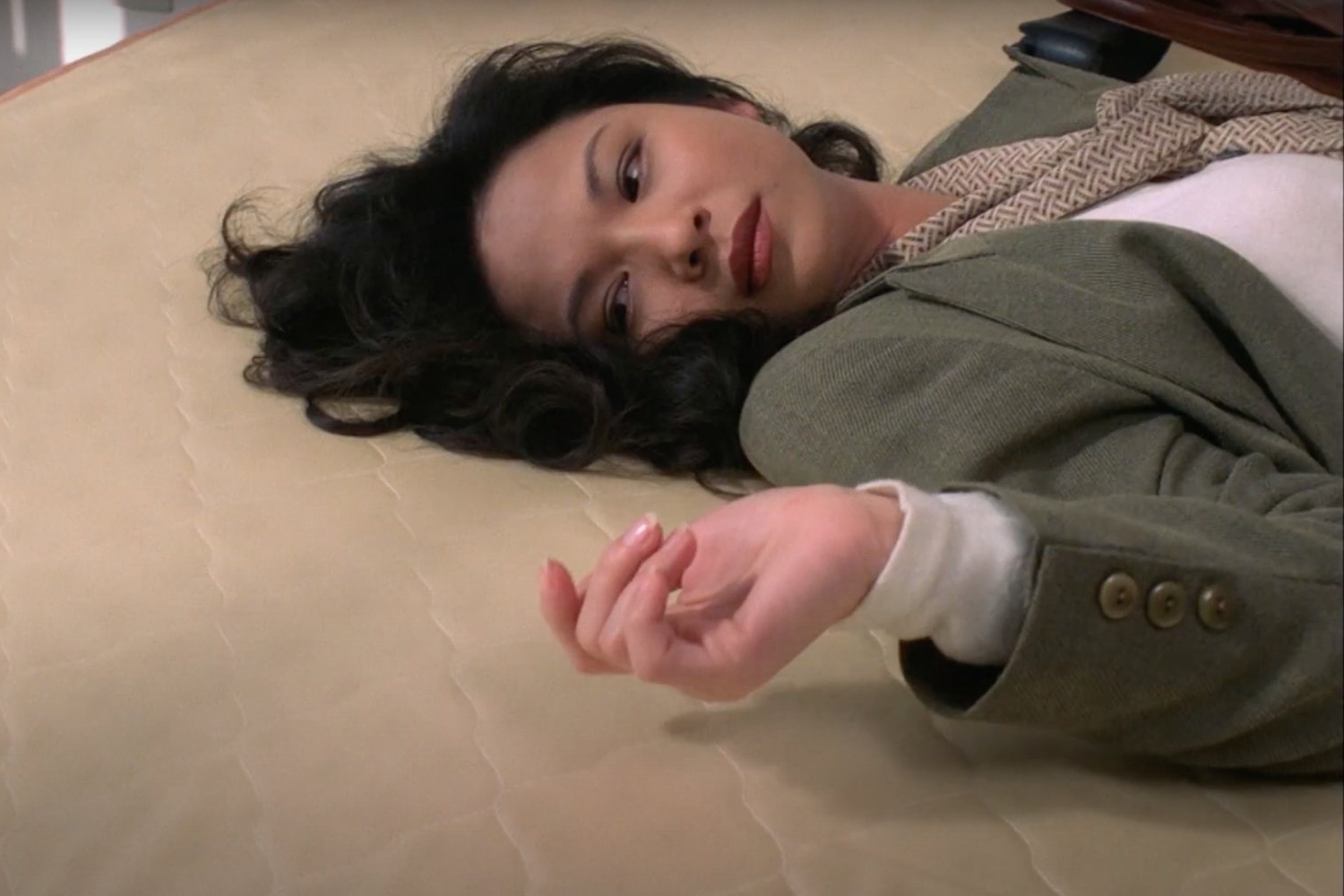

Meanwhile, some place else in Taipei, we’re treated to a delectable bit of flirtation in a food court, where Mei-mei (Yang Kuei-mei) takes a seat on the table next to Ah-jung (Chen Chao-jung). His eyes flash intermittently at her. Her own eyes drift vaguely in his direction, but she pretends not to notice his attention — or rather, she lets him know that she’s pretending not to notice. What follows is a slow-motion game of cat and mouse: Mei-mei wanders past a cinema and a department store, Ah-jung follows; Ah-jung goes into a phone booth, Mei-mei lingers outside. Not a word is said between them, only the most subtle acknowledgement of each other’s presence. But soon Mei-mei is leading Ah-jung into an apartment — the very same apartment in which Hsiao-kang has rather half-heartedly attempted suicide. As the couple begin to have sex, we cut to an understandably bewildered Hsiao-kang tip-toeing, cartoon-like, across the hallway to make his escape.

Urban alienation, isolation, loneliness — these are the kind of topics that usually get brought up when discussing Vive l’Amour. All valid entry points, but let’s not forget that it’s also a darkly funny movie; the lightly absurd aforementioned set-up is not the only time a character will be comically walked in on, resulting in them peeking round corners, hiding under beds, scrambling over slippery floors. The same could be said of Tsai’s 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn, which is “about” spectrality, decay, and the Death of Cinema, but which also dedicates a fair amount of its runtime to quietly hilarious skits concerning one of its character’s frustrated adventures in cruising. My point isn’t that Tsai is some unsung master of slapstick, only that writing concerned with the director’s reputation for weighty themes, stylistic austerity, and relaxed pacing too often overlooks the fact that his films are made with a light touch, even a certain playfulness.

Mei-mei, we find out soon enough, is a real estate agent, hence the keys for the apartment that she sometimes uses for late-night trysts. Her days are spent traveling between various empty properties and failing to convince unenthused potential buyers. Ah-jung is an unlicensed street peddler of imported women's clothes in one of Taipei's night markets. He also manages to pocket a key to the apartment, setting in motion more hide-and-seek shenanigans. Hsiao-kang is a salesman of burial vaults for a crematorium, and his lonely antics in the apartment are perhaps the most affecting, if curious. In one scene he transforms a melon into a romantic lover, then a bowling ball. In another, he dons a slinky black dress and feather boa and starts doing push-ups. Later, after Ah-jung discovers Hsiao-kang in the apartment, a kind of camaraderie develops between the two, though for Hsiao-kang it’s really unrequited, or at least unacknowledged, desire. A single kiss, gently planted on the lips of the sleeping Ah-jung, effectively constitutes the emotional climax of the picture, that is if a film so patient, so sparse, could be said to feature something like that.

Over the course of the film, we get physically and emotionally close to this trio. The camera caresses their bodies, observes them in the most private of moments, and yet a certain distance remains, between us and the characters as much as the characters and each other. We are to understand that all three are desperately lonely, but we only get glimpses of their desires that might provide some form of escape.

What, then, to make of the film’s final scene? Mei-mei, who has left the apartment after sleeping with Ah-jung again, makes her way through Da’an Park. The choice of location is a loaded one: the park was built in 1994 after the controversial eviction of 12,000 squatters from an informal settlement on the site, and is thus emblematic of Taipei’s gentrification. Still-incomplete at the time of filming, the scarred, purgatorial wasteland Mei-Mei wanders through can’t help but feel like the logic of the spectral, liminal apartment — pristine but characterless, a space defined by its absences and the connections it fails to facilitate — infecting the city at large.

Mei-mei takes a seat on a bench and, in an unbroken take lasting over five minutes, begins to cry. Weep, really, almost uncontrollably. After a while she stops crying, composes herself, lights a cigarette. But then she cries some more. It’s here the film ends, and it’s hard to know what to make of the scene. A welcome moment of catharsis? A sign of more misery to come? Either way, it’s a difficult scene to watch, in part because its length makes us acutely aware we’re watching, but asks us to surrender ourselves to the shot’s raw emotional power anyway. It’s a risky filmmaking gamble by Tsai, one that pays off as spectacularly as the film’s many other indelible moments.