Blog Post

January 11, 2024

January 11, 2024

Before getting into my picks for the best films of the past year, it’s worth taking a moment to appreciate the oft-forgotten middlebrow movies — or outright stinkers — that tell us more about the state of the art (or at least the industry) than any of their more reputable cousins. Take the ending of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, which captures so much of the past fifteen years or so of American blockbuster filmmaking in a single punch. In the film’s final act (massive spoilers, by the way), archaeologist/Nazi-magnet Indiana Jones (played by Harrison Ford for the fifth time since 1981) is transported to the year 212 BC through a fissure in time that is, now the baddies have been defeated, threatening to close. But Indy doesn’t want to go back to his own time. In fact, he practically begs his companion to let him stay; the past, he thinks, is where he belongs.

What an ending! Indiana Jones — emblem of nostalgia not only for the ’80s, but also for the ’40s adventure serials creators Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were pastiching in the first place — can be left in the past, can finally become one of the very relics he’s spent his career searching for. Except that’s not the film’s ending, because Indy’s younger companion abruptly punches him in the face and forcibly drags him back to the future. He wakes to a very different kind of happy ending, one in which he’s reunited with his ex-wife Marion, a character we haven’t even yet seen in this film, played by fan-favourite Karen Allen. Nostalgia wins out after all. Honestly, there’s something quite funny about the bluntness with which the film admits that the Walt Disney Company will simply not let this man die while there’s money to be made.

Sticking with cash-grabbing ploys involving digging up old dudes, I enjoyed the chaos around the DC superhero movie The Flash, whose entire marketing centred on the return of Michael Keaton as Batman (because its actual star had been on a crime spree). Of course, the thing we see on screen often isn’t Keaton at all; like the youthful Harrison Ford in the opening of the new Indiana Jones, who croaks with the voice of a man three times the age of his uncanny GCI clone, Keaton flings himself around The Flash’s various non-spaces courtesy of a weightless CGI puppet. It’s at least a fate slightly more dignified than the actually-dead actors from other DC universes (properties)— George Reeves, Adam West, Christopher Reeve — digitally reanimated for cameos in the film’s finale. It’s all rather fitting: upon release The Flash was itself a zombie movie, one of the final instalments of a franchise that had already committed to wiping the slate clean and starting over.

The Flash was not the worst superhero movie of the year — that would be the abysmal Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania — but it was representative of the worst impulses of a genre that has dominated this millennium’s global box office, especially as confirmation that the multiverse trend of recent years has been just another avenue for exploiting a culture hooked on nostalgia. Admittedly The Flash was a flop, and even DC’s rivals Marvel are stumbling at the box office — though Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3 demonstrated that if these things are competently made, they’ll still do well and be adored by most critics. Personally, I wasn’t convinced by the Guardians’ pivot to hardcore sentiment; I found myself intermittently taken out of the film by thoughts about how strange it was to be watching a cutesy anthropomorphic Racoon voiced by Bradley Cooper being tortured for my enjoyment. (I had similar feelings about the treatment of Carey Mulligan’s character in Cooper’s own directorial effort, Maestro.)

Oppenheimer - Pacifiction - Asteroid City - The Zone of Interest

I’m admittedly picking on easy targets, and don’t want to paint a picture of a totally dire mainstream – so, on to the good stuff. I thoroughly enjoyed watching a flesh-and-bones Tom Cruise continue to hurl himself around in Mission Imposible: Dead Reckoning; these guys have landed on a formula, and it’s not a bad one. Emma Seligman’s Bottoms, a refreshingly stupid spin on the high school comedy, was a great vehicle for the immense comic talents of Rachel Sennott and Ayo Edebiri. And there was one superhero movie that I loved this year, the animated sequel Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse — a film somehow even more wildly creative than its predecessor. I also had a great time catching a sold-out, pinked-out screening of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie on opening weekend, even if the film’s corporate-approved autocritique does very little that wasn’t done better and more succinctly in the 1994 Simpsons episode “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy.” (For a very different take on many of the same themes, I would recommend Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things, a film I loved and then went to war with.)

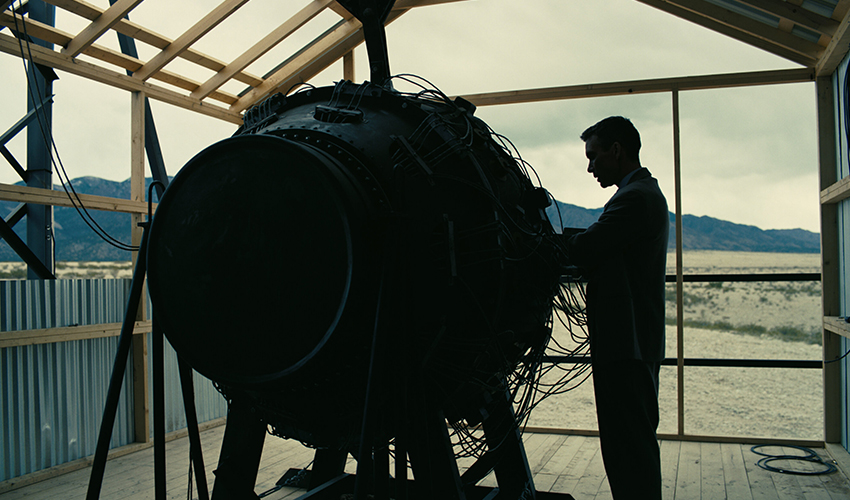

Much to my surprise, my preferred Barbenheimer flick was feel-bad hit of the summer Oppenheimer, Christopher Nolan’s despairing portrait of the so-called father of the atomic bomb. Apart from anything else, the film is an astonishing feat of editing — a single, tumbling montage that never loses momentum over its three hours. The bar is obviously quite low, but I was also just quite amazed to see a historical blockbuster of this scale unequivocally state that the dropping of the atom bomb was both evil and wholly unjustified, that the McCarthyist hounding of Oppenheimer was also wrong, and that no amount of guilt and half-hearted martyrdom could ever redeem a man — and a country — who lacked real moral conviction about anything. For a more muted but no less unnerving film that also touches on nuclear anxiety, I’d also recommend Pacifiction, a gorgeously shot film that’s also director Albert Serra’s best yet.

Come to think of it, distant atomic testing also existentially punctuates Asteroid City, a playfully metacinematic movie that doubles the mysteries of extraterrestrial life with the those of art itself. It’s filmmaker Wes Anderson’s finest since 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. More impressively, Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days — about a Tokyo toilet cleaner who manages to find the simple pleasures of routine — is probably his best fiction film in over thirty years. I can see how these films could be accused of being too clean to really challenge, but I do appreciate that both works, in their different ways, are grappling honestly with how we might glean meaning from a chaotic and depressing world.

By contrast, The Zone of Interest was one of the most viscerally unpleasant experiences I had all year. Director Jonathan Glazer has gutted Martin Amis’ novel — about the family of a Nazi commandant living next-door to Auschwitz — of almost all of its plot, retaining only the setting and wonderfully euphemistic title. The constant juxtaposition between the domestic bliss on one side of the camp’s wall and the horrific sounds that seep over from the other is profoundly disturbing, though thankfully Glazer plays very little on the kind of smirking ironies could easily have built a film around. Rather, this is a deliberately paced film that provocatively challenges us to recognise in the mundanities of Nazi Germany something of our own lives.

Evil Does Not Exist - How To Have Sex - Footsteps - Incident

A very different kind of patient, political filmmaking can be found in Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Evil Does Not Exist, which sees a rural community threatened by the imminent construction of an intrusive “glamping” site. The shocking and enigmatic ending is one I’m still turning over. Unexpectedly, I was similarly unnerved by the final scenes of Richard Linklater’s otherwise uproariously funny (and genuinely sexy) Hit Man, a rom-com about a dorky psychology professor who moonlights for the police as a fake hitman, and in doing so exposes something of the malleability of self. It’s typical of Linklater to sneak in some compelling philosophy and moral quandaries into the most crowd-pleasing film of the year.

A pair of debut features have inspired some of the best conversations I’ve had with friends this year. Molly Manning Walker’s How to Have Sex is an alarmingly well-observed portrait of the gendered horrors of teendom via an extremely British rites-of-passage holiday. I sincerely hope it’s screened in schools across the country. Similarly honest is Past Lives, Celine Song’s tale of childhood sweethearts reunited. It’s a film that smartly trips up expectations — though for such a seemingly straightforward narrative, my friends’ interpretations and emotional responses have differed vastly.

Some of the most personal films I saw this past year weren’t screened in a cinema, and one wasn’t really a film at all. In As Mine Exactly, a single viewer sits opposite filmmaker Charlie Shackleton and listens as he shares his childhood recollections of the onset of his mother’s epilepsy, accompanied by desktop-doc footage watched on a VR headset. It’s unsettling and moving in equal measure — and a work I haven’t stopped thinking about. More oblique but similarly poignant was Fiona Tan’s gallery piece Footsteps, which juxtaposes letters sent to the artist by her father in the 1980s with found footage of Dutch life and industry nearly a hundred years earlier, exploring histories personal and political. The conceit is reversed in Steve McQueen’s Occupied City, which combines footage shot in modern-day Amsterdam with narration detailing the atrocities and acts of resistance that occurred in those same places during the Second World War. It makes for an interesting meditation on the relationship between the past and the present, though I was more affected by McQueen’s much shorter film Grenfell, which comprises of a single shot of the then-recently burned tower taken from a helicopter.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Bill Morrison’s latest documentary Incident— about a black man killed by the police on the streets of Chicago in 2018 — was another of the most urgently political films I saw this year. Morrison recreates the event using surveillance and bodycam footage, allowing us see institutional fictions (“he pulled a gun on us!”) and justifications take shape in practically real time; it’s essential viewing. I was also impressed by the immediacy of Anders Hammer’s The Takeover, documenting the protests and counter-protests that occurred as the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan, and Mstyslav Chernov’s harrowing 20 Days in Mariupol, shot by journalists documenting civilians caught in Russia’s siege of the city.

Notes from Gog Magog - The Boy and the Heron - Showing Up - Anatomy of a Fall

In the year that AI image-making was properly democratised, I unsurprisingly managed to see a lot of terrible AI art. (In tribute, may I present the header image at the top of this piece.) One exception was Riar Rizaldi’s short Notes from Gog Magog, an experimental ghost story exploring contemporary tech capitalism which exploits the Cronenbergian potential of AI fantastically. On a more tangible level, Aaron James Robertson’s Rea’s Men creatively evokes a kind of purgatory in which it explores masculine cycles of violence and the legacies of Windrush. I also caught up with a lot of innovative short video essays this year: Maryam Tafakory’s chaste/unchaste, Chloé Galibert-Laîné’s GeoMarkr, and the final entries in Johannes Binotto’s series Practices of Viewing. My favourite was probably Richard Misek’s A History of the World According to Getty Images, an investigation into the privatisation of the so-called public domain that slyly works against what it’s describing.

Of the feature documentaries I saw this year, one stood out in particular. Filmmaker Kit Vincent found out he had terminal cancer aged 24, and in his debut Red Herring he trains his camera on the most important people in his life in an attempt to explore how they're dealing (or not dealing) with the diagnosis. Inevitably, the process also results in a self-portrait of its director as he tries to figure out what sort of legacy he wants to leave behind. The film’s biggest surprise is that it’s as funny as it is devastating. The Boy and the Heron, from master animator Hayao Miyazaki, also finds its maker grappling with legacy — and predictably ends on a spectacular note that manages to feel both pessimistic and optimistic. If this is indeed Miyazaki’s last film, it’s a poignant note to wrap up a remarkable career on.

Todd Field’s Tár would’ve topped my list for last year’s best films, but I didn’t manage to see it in time due to its later UK release; it’s the same reason I haven’t seen new films from Hirokazu Kore-eda, Andrew Haigh, Alice Rohrwacher, and Radu Jude yet. Amazingly, Kelly Reichardt’s 2022 film Showing Up still hasn’t received a cinema release here, and probably never will. It’s a real shame, because it’s one of the better films I’ve seen about being an artist. A few films I saw at the end of last year are now becoming widely available; I’d still recommend Ann Oren’s delightfully strange Piaffe, as well as Jumana Manna’s skilful blend of documentary and fiction Foragers — a film about the systematic erasure of Palestinian culture that has only become more essential as Israel’s barbaric treatment of the Palestinian people has sharply escalated.

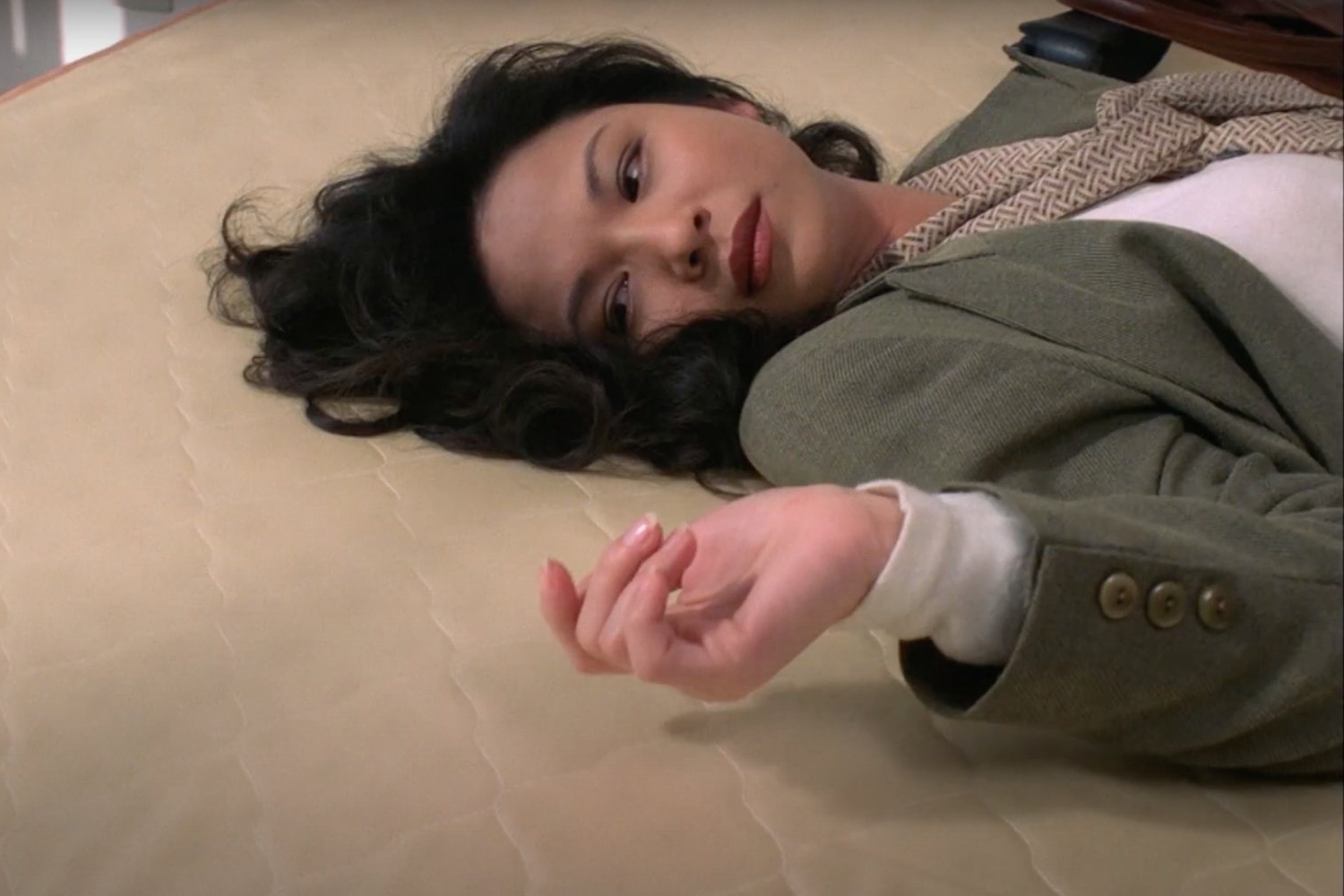

My favourites of the year were two fascinating films about the essentially fictive nature of the truth and the extent to which you can really ever know someone: Todd Haynes’ slippery swipe at the true crime genre May December and Justine Triet’s did-she-do-it courtroom drama Anatomy of a Fall. Aside from being astonishing feats of direction, acting, and especially writing — films unafraid to introduce complication upon complication — they’re also both just supremely entertaining movies that I know I’ll be watching again and again.

Finally, twenty new-to-me films I loved this year:

- Ace in the Hole (1951, dir. Billy Wilder)

- Ball of Fire (1941, dir. Howard Hawks)

- Blight (1996, dir. John Smith)

- Bound (1996, dir. Lana and Lilly Wachowski)

- Chan Is Missing (1982, dir. Wayne Wang)

- The Exquisite Corpus (2015, dir. Peter Tscherkassky)

- The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (1962, dir. Karel Zeman)

- Frank’s Cock (1994, dir. Mike Hoolboom)

- Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990, dir. Joe Dante)

- Irma Vep (1996, dir. Olivier Assayas)

- Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975, dir. Chantal Akerman)

- The Lady Eve (1941, dir. Preston Sturges)

- La Ronde (1950, dir. Max Ophüls)

- Looking for Langston (1989, dir. Isaac Julien)

- Make Way for Tomorrow (1937, dir. Leo McCarey)

- Millennium Mambo (2001, dir. Hou Hsiao-hsien)

- Ordet (1955, dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer)

- Variety (1983, dir. Bette Gordon)

- Yi Yi (2000, dir. Edward Yang)

- You, the Living (2007, dir. Roy Andersson)