Back to the Movies: Goodbye, Dragon Inn

After months of pandemic-induced closures, my first trip back to the cinema in May 2021 was a screening of Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn at the BFI Southbank, London. I was, to be perfectly honest, somewhat apprehensive about going; this was my first time at an indoor event in ages, and it was a sold-out screening – meaning, as full as it could be with social distancing in place. Two factors convinced me to go. Firstly, the strange poetry of seeing a film about moviegoing itself; Goodbye, Dragon Inn is set in a cinema. And secondly, because the film was being introduced by Peter Strickland – a director whose films I love – as part of the BFI’s “Dream Palace” season, for which filmmakers were asked to select the one film they’d most like to see on the big screen.

As it turned out, Strickland’s introduction would prove as memorable as the film itself. In a series of hilarious confessions, Strickland admitted that Goodbye, Dragon Inn wasn’t his first choice of film; that in fact he hadn’t seen the film at all and had picked it on a whim because the Wikipedia entry made it sound interesting; that he’d purchased a DVD copy and tried to watch it at home, but had been repeatedly distracted by his young children (at this point, he brandished the DVD case and started reading from the enclosed booklet); that he had seriously contemplated lying about all this so as not to damage his cinephile credentials; and finally that he wasn’t going to stay for the screening because he had somewhere more important to be. The director promised he’d get round to watching it later in the summer, and sheepishly shuffled out the fire exit.

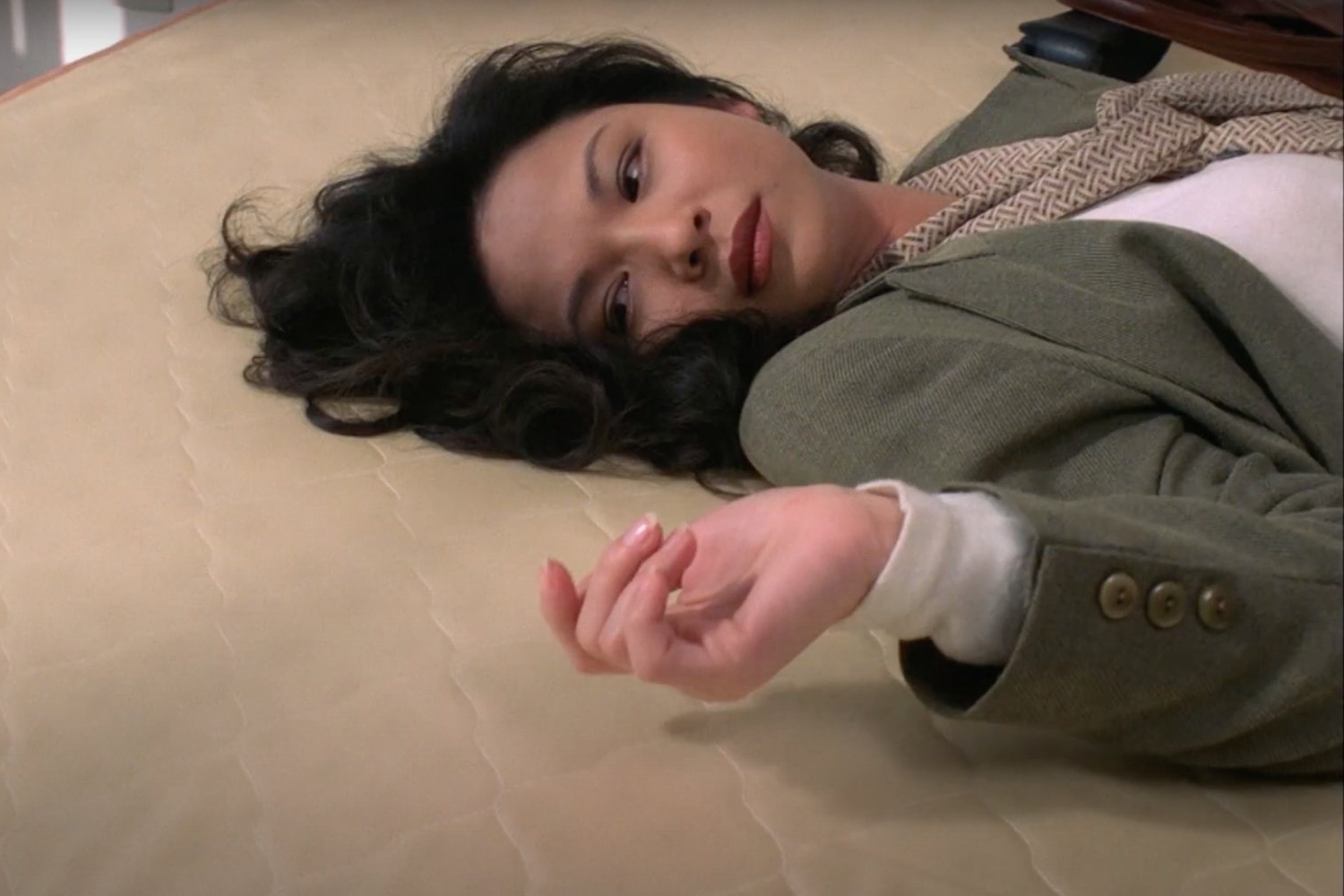

It was a perfect opening – you could practically hear the audience deflating, once the giggles had subsided – to what turned out to be a perfect movie. Goodbye, Dragon Inn takes place over the course of a single rainy night at the Fu-Ho Grand, a large, borderline-dilapidated urban theatre screening the 1967 wuxia epic Dragon Inn on the eve of what a sign outside optimistically describes as a “Temporary Closure”. A brief prologue shows the cinema in its heyday, packed out for a showing of the same film, but at the turn of the millennium the Fu-Ho Grand has only a handful of patrons, most of whom drift in and out of the auditorium.

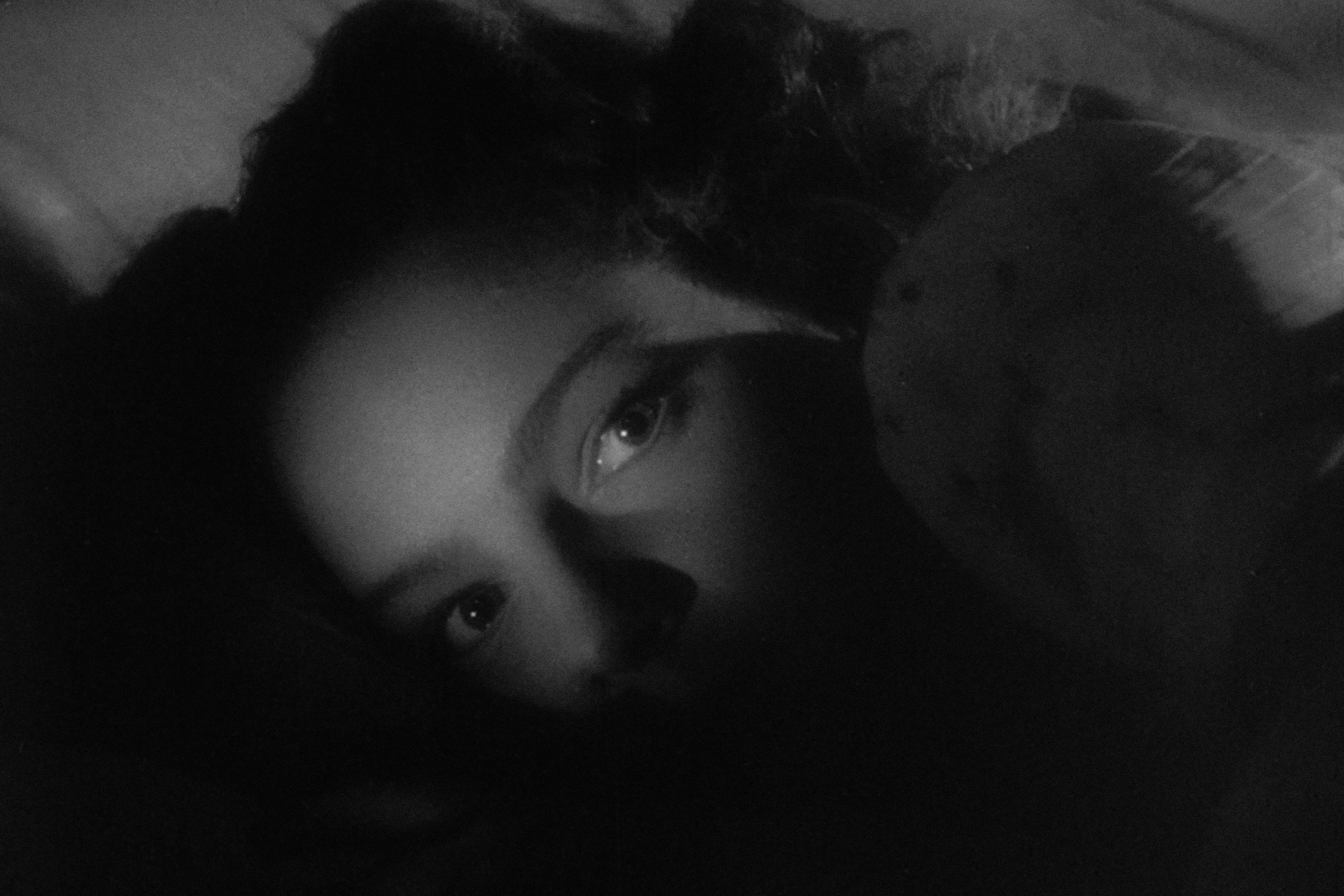

Actually, most of the “action” – glacially paced, this is hardly a film about things happening – takes place in the box office, projection booth, bathroom, as well as the labyrinthine collection of corridors and storerooms. Two characters emerge as the film’s focal points: a ticket seller with a leg brace, who slowly makes her way around the theatre in search of the elusive projectionist, and a hapless Japanese tourist looking to get laid; the cinema is, we quickly learn, now primarily a cruising spot for gay men. The only audience members who seem entirely invested in the film are Miao Tien and Shih Chun, the now-elderly stars of Dragon Inn, as well as Miao’s young grandson.

Clearly, Goodbye, Dragon Inn is an elegy for the cinema, and in Tsai’s hands the movie theatre becomes a ghostly space, a space of phantom desire – desire for sex, but also for companionship, and for the ambivalent sense of community afforded by (disappearing?) moviegoing rituals. For all its obvious melancholy, it’s also a warm and unexpectedly funny film that seems enamoured by the idea that even in its dying days the cinema continues to make room for society’s outsiders. The sense of loss isn’t exactly that the Fu-Ho Grand is far from its former glory – it’s that it soon might not be there at all.

Seeing Goodbye, Dragon Inn earlier this summer presented a kind of paradox: there we all were, watching a film about the supposed decline of the cinema, at a sold-out screening at the recently renovated BFI Southbank. The nice, over-easy thing to say would be that the film’s pessimism has proved misguided. But the cinemagoing experience is under threat; all the more noticeably since it’s been brought into competition with streaming, whose primary goal seems to be the flattening of all screen media, art or otherwise, into “content”. The BFI is one of the only cinemas in London still likely to show a film like Goodbye, Dragon Inn – let alone the original Dragon Inn – and the pandemic has put theatres, multiplex chain and tiny independent alike, in a more precarious situation than ever before.

The film, and my experience of watching it after months of closures, drilled home the importance of the cinema itself, and not just because Goodbye, Dragon Inn is particularly suited to the sensory deprivation afforded by the movie theatre. It made me realise more clearly than before that a film is never just what’s playing on the screen: it’s picking your favourite spot, getting comfy as the trailers play; it’s excitedly asking “what did you think?” as the credits roll; it’s the kid loudly crunching on popcorn, the man with the freakishly loud laugh, the woman with the massive hair who sits in front of you right as the movie starts; it’s the minor scuffle that breaks out when one audience member complains that the film is in black and white (NYC, 2019, The Lighthouse); it’s the first/last date you went on, the kiss in the dark – or maybe you were just cruising. It’s the snatched glances at strangers, all grinning because the director is telling us he hasn’t watched the film he’s introducing.