The Eternal Daughter

The first surprise of Joanna Hogg’s latest film is that it’s a follow-up of sorts to her brilliant semi-autobiographical two-parter The Souvenir (2019 and 2021) — not so much a straightforward sequel as a present-day coda, again examining the process and consequences of extracting art from life. Those films formed a portrait of a budding filmmaker, Julie, in 1980s London, and this time it’s Tilda Swinton playing a grown-up version of the character (originally played by her actual daughter Honor Swinton Byrne), as well as reprising her role as Julie’s ageing mother Rosalind.

The Eternal Daughter enfolds entirely over a few days in a remote country manor — now a hotel — that once belonged to Rosalind’s aunt, and that the daughter and mother are visiting to celebrate the latter’s birthday. Julie also has a not-so-secret ulterior motive: she’s come to write a film about the relationship between the two. But Julie doesn’t seem to know where to begin, and as the old, Gothic house brings back memories for Rosalind, not all of them pleasant, she begins to get the sense that the eerily empty hotel is haunted.

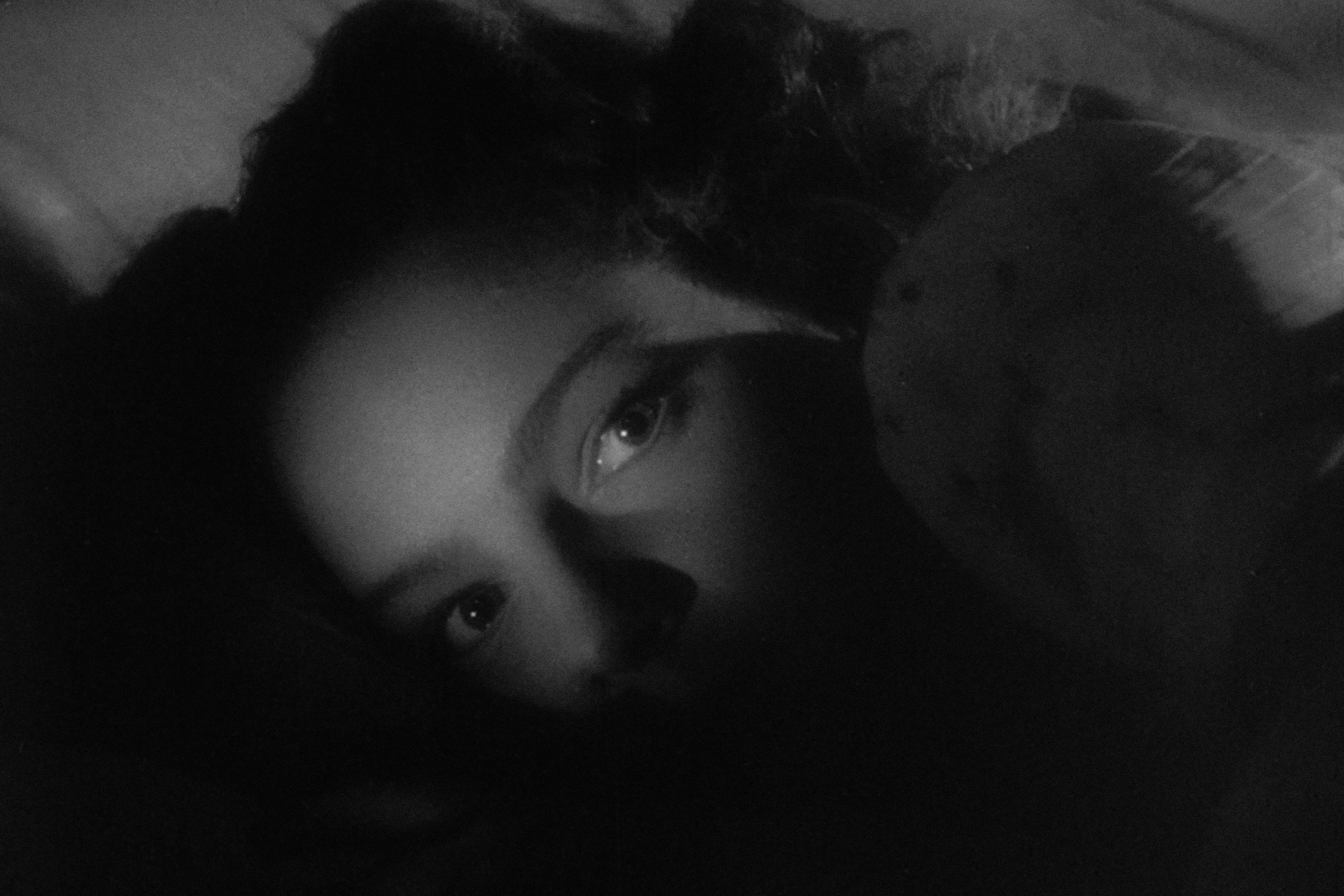

Accordingly, Hogg’s usual approach — an unusual application of social realist style to the upper-middle-class experience — is complimented with a cheeky sprinkle of horror tropes: unexplained bumps in the night, creeping fogs, patchy phone signal, and so on. (The otherworldly emerald glow that illuminates the hotel’s corridors even suggests a hint of giallo; cinematographer Ed Rutherford makes astonishingly good use of artificial light throughout). The foreboding atmosphere is cemented by the periodic deployment of Bartók’s “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta,” which Kubrick used to similarly creepy effect in The Shining — though Bartók was also the favoured composer of Anthony, Julie’s doomed lover in The Souvenir, suggesting another intertextual ghost lurking.

![]()

By casting Julie as her mother’s literal doppelgänger, Hogg at first seems merely to be underlining the tired point, as per Oscar Wilde, that all women become their mothers. Actually, the film cleverly uses Swinton’s dual role to show the exact opposite — that, despite their superficial similarities, a gulf of understanding exists between the pair. Rosalind’s doleful reminiscing only serves to show how little Julie actually knows about her mother’s life, forcing her to reconsider whether she has a right to make a film about her in the first place.

What we see is a caring but terse relationship that neither party seems particularly comfortable navigating. Julie is fussing and over-apologetic, while Rosalind’s reticence undercuts her ostensible reassurance; both are excessively courteous and stiff, constantly deferring to each other in hopeless attempts to please (“What do you think, mum?” asks Julie. “What do you think?” her mother replies). Hogg lets the discomfort build until the film reaches an emotional climax in which the seemingly banal act of delivering a birthday cake becomes acutely painful for characters and audience alike.

Swinton, predictably, is superb in both roles. It’s her film through and through, although newcomer Carly-Sophia Davies threatens to steal the spotlight in the largely comic role of the hotel’s brusque young concierge; amusingly, Julie can’t seem to grasp why a twenty-something stuck in a dead-end job in the middle of nowhere is entirely uninterested in indulging her toffish pleasantries. Both Julie and Rosalind do, however, find a confidant in the hotel’s kindly caretaker, played with real warmth by Joseph Mydell.

If there’s a criticism, it’s only that The Eternal Daughter feels ever so slightly lightweight coming off the back of a career-defining statement like The Souvenir; certainly, the film is less ambitious, and working within more familiar genre parameters. But as a standalone study of a mother-daughter relation, Hogg’s latest is an affecting little slice of metacinema — witty, ruminative, sad, and this time a little spooky.

The Eternal Daughter enfolds entirely over a few days in a remote country manor — now a hotel — that once belonged to Rosalind’s aunt, and that the daughter and mother are visiting to celebrate the latter’s birthday. Julie also has a not-so-secret ulterior motive: she’s come to write a film about the relationship between the two. But Julie doesn’t seem to know where to begin, and as the old, Gothic house brings back memories for Rosalind, not all of them pleasant, she begins to get the sense that the eerily empty hotel is haunted.

Accordingly, Hogg’s usual approach — an unusual application of social realist style to the upper-middle-class experience — is complimented with a cheeky sprinkle of horror tropes: unexplained bumps in the night, creeping fogs, patchy phone signal, and so on. (The otherworldly emerald glow that illuminates the hotel’s corridors even suggests a hint of giallo; cinematographer Ed Rutherford makes astonishingly good use of artificial light throughout). The foreboding atmosphere is cemented by the periodic deployment of Bartók’s “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta,” which Kubrick used to similarly creepy effect in The Shining — though Bartók was also the favoured composer of Anthony, Julie’s doomed lover in The Souvenir, suggesting another intertextual ghost lurking.

By casting Julie as her mother’s literal doppelgänger, Hogg at first seems merely to be underlining the tired point, as per Oscar Wilde, that all women become their mothers. Actually, the film cleverly uses Swinton’s dual role to show the exact opposite — that, despite their superficial similarities, a gulf of understanding exists between the pair. Rosalind’s doleful reminiscing only serves to show how little Julie actually knows about her mother’s life, forcing her to reconsider whether she has a right to make a film about her in the first place.

What we see is a caring but terse relationship that neither party seems particularly comfortable navigating. Julie is fussing and over-apologetic, while Rosalind’s reticence undercuts her ostensible reassurance; both are excessively courteous and stiff, constantly deferring to each other in hopeless attempts to please (“What do you think, mum?” asks Julie. “What do you think?” her mother replies). Hogg lets the discomfort build until the film reaches an emotional climax in which the seemingly banal act of delivering a birthday cake becomes acutely painful for characters and audience alike.

Swinton, predictably, is superb in both roles. It’s her film through and through, although newcomer Carly-Sophia Davies threatens to steal the spotlight in the largely comic role of the hotel’s brusque young concierge; amusingly, Julie can’t seem to grasp why a twenty-something stuck in a dead-end job in the middle of nowhere is entirely uninterested in indulging her toffish pleasantries. Both Julie and Rosalind do, however, find a confidant in the hotel’s kindly caretaker, played with real warmth by Joseph Mydell.

If there’s a criticism, it’s only that The Eternal Daughter feels ever so slightly lightweight coming off the back of a career-defining statement like The Souvenir; certainly, the film is less ambitious, and working within more familiar genre parameters. But as a standalone study of a mother-daughter relation, Hogg’s latest is an affecting little slice of metacinema — witty, ruminative, sad, and this time a little spooky.