The Marvel Cinematic Universe and

Neoliberal Ideology [Excerpt]

Unpublished

August 16, 2022

August 16, 2022

This extract is taken from the second chapter of my master’s dissertation, which takes as its focus the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), a shared narrative storyworld and hugely successful transmedia franchise currently dominating the global cinema box office. Taking an approach influenced by film studies alongside a cultural studies framework that views popular culture texts as sites for negotiating meaning, I understand the selection of films analysed as “teaching machines” (Giroux) that attempt to legitimise the dominant ideology at present, neoliberalism. Specifically, I argue that a recent development in the superhero blockbuster is the integration and careful narrative management of ideological critique that seeks to guide politized readings of the texts in question — but which, upon closer inspection, reveals the systemic closing off of alternatives to neoliberalism.

“The price of freedom is high. Always has been. And it’s a price I’m willing to pay.”

— Captain America in Captain America: The Winter Soldier

In March 1941 — a full nine months before the United States joined the Second World War — the cover of Captain America #1 depicted the star-spangled superhero punching Adolf Hitler in the face. “The hyperbolic cover”, writes Jeffery Brown, “and the concept of America joining the war, appealed to many Americans and was an immediate success, selling over a million copies of the first issue alone” (93). While, as we’ve seen, superheroes like Iron Man and Spider-Man can be read as standing in for the US, Captain America more explicitly represents the “nationalist superhero” as identified by Jason Dittmer — embodying the nation-state and protecting its abstract ideals, not only its population. While the first adaption of the character in the MCU, Captain America: The First Avenger, largely accepts this propagandistic role for the hero — albeit with a healthy dose of irony — its sequel, Captain America: the Winter Soldier, sets out to challenge the character’s relationship to American exceptionalism, particularly by engaging post-9/11 anxieties surrounding mass surveillance.

In this chapter, I read The Winter Soldier with Fredric Jameson’s commentary on the conspiracy narrative in mind, and argue that the film’s supposedly subversive evocation of contemporary politics falls apart upon closer inspection, once again amounting to a defence of neoliberalism. Created in 1966, at the height of the civil rights movement, Black Panther represents a very different kind of nationalist superhero, embodying political debates surrounding Black nationalism.[i] The comic book’s recent film adaptation, even more forcefully than The Winter Soldier, uses its villain to evoke historical and contemporary politics — engaging with issues of (neo)colonialism, civil rights struggles, Pan-Africanism, and Black radicalism — only to once again invalidate criticisms of the status quo through narrative management of violence. Black Panther also, however, represents a new development in the MCU: the appropriation of the villain’s objectives into the hero’s (and viewer’s) sympathies, albeit in heavily compromised form stripped of their radical energy.

Conspiracy and Captain America: The Winter Soldier

In Captain America: The First Avenger, we witness the transformation of the scrawny civilian Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) into the “super soldier” Captain America.[ii] The film is, in many ways, a typical “nostalgia film” in the sense described by Jameson, employing recognisable signifiers of “pastness” while simultaneously emptying the period depicted of its history by means of such “aesthetic colonization” (Postmodernism 19). The First Avenger adopts an ironic stance to nationalism, as is best exemplified by a musical montage that sees Rogers selling war bonds on stage and appearing in hammy propaganda newsreels, ridiculing the jingoistic excesses of 1940s America and its passion for profitable mythmaking (fig. iii).

At the same time, however, it readily promotes a simplified depiction of “good” and “bad” agents of war, leading Terence McSweeney to argue that the film represents a “fantastical rewriting of World War Two that goes to great lengths to be a distinctly depoliticised one” (129). That the elite unit of heroes pulled together by Captain America is a multicultural group, including a Japanese-American and an African-American soldier, sidesteps both issues of racism within the US (whose military was not desegregated until 1948) and the moral atrocities committed by America in the Pacific War. Likewise, the “Nazis” (represented here by their fictional science research division “Hydra”) are depicted, as they are in the Indiana Jones series and many other American blockbusters, as representing an abstract “pure evil” with the racial component of their crimes omitted; they are identified by the film as “bullies,” though not orchestrators of the Holocaust. This sanitisation of historical reality is made more troubling by the fact that, to defeat Nazism in the MCU’s revisionist account of World War II, the US resorts to eugenics, creating a blue-eyed, blonde-haired Übermensch. As in the Iron Man and Spider-Man films, The First Avenger continues to promote the idea that certain practices and technologies — this time, militarised biotechnologies — are only morally problematic when out of American hands.

While Captain America’s first outing attempts to depoliticise its ostensibly political content, it’s sequel, in stark contrast, goes out of its way to be perceived as “about” politics — indeed, as itself a political film. The plot of Captain America: The Winter Soldier concerns the efforts of the espionage agency S.H.I.E.L.D. to commence Project Insight. This involves the deployment of three flying aircraft carriers (“Helicarriers”) linked to spy satellites, which have been designed to pre-emptively eliminate threats, Minority Report style. Rogers’ doubts with the project — “I thought the punishment usually came after the crime,” he objects — are substantiated when he discovers that S.H.I.E.L.D. has been infiltrated by Hydra under the direction of senior official Alexander Pierce (Robert Redford). Using a sophisticated algorithm designed by Arnim Zola (Toby Jones), Hydra are able to identify and target their own threats — both in the present and, as Hydra mole Jasper Sitwell (Maximiliano Hernández) reveals, in the future:

Rogers: In the future? How could it know?

Sitwell: How could it not? The twenty-first century is a digital book. Zola told Hydra how to read it. Your bank records, medical histories, voting patterns, emails, phone calls, your damn SAT scores! Zola’s algorithm evaluates people’s past to predict their future.

Rogers: And what then? […]

Sitwell: Then the Insight helicarriers scratch people off the list. A few million at a time.

The Winter Soldier deliberately taps into key post-9/11 anxieties concerning surveillance and the stripping back of civil liberties, which might be seen as relating broadly to Bush’s 2001 Patriot Act and its massive expansion of the investigative powers of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and more specifically to 2012 disclosures concerning the Obama administration’s use of drone strikes and the establishment of its “Disposition Matrix,” a database used to track, capture or kill suspected enemies of the United States, with targets often chosen based on controversial metadata analysis (Weber 112). Notably, the film was released less than a year after Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations that, in addition to monitoring “threats,” the National Security Agency (NSA) was covertly subjecting its own citizens to mass surveillance.

More so than previous MCU films, which were happy for politics to play a background role that helped ground the film in reality, The Winter Soldier actively invites readings that position the film as political allegory for troubled times. Upon the film’s release, reviewers were quick to note the relevance of contemporary politics to the film. Buzzfeed’s Alison Willmore called The Winter Soldier “the most political movie in the Marvel Cinematic Universe … a blockbuster-as-thriller that manages to echo all sorts of contemporary fears about surveillance, secrecy, and the fundamental untrustworthiness of large institutions,” while Den of Geek’s Ryan Lambie described it as a “political thriller … that is thought-provoking and perhaps even subversive.”

Lambie’s description of the film as a “political thriller” is particularly revealing, in that it suggests that the film’s claim to “politics” might be as much a matter of genre convention as it is a genuine exploration of themes plucked from the headlines. Many reviewers pointed out the specific resemblance between The Winter Soldier and the conspiracy thrillers of the 1970s — films like The Parallax View (1974), Three Days of the Condor (1975), All the President’s Men (1976) and Marathon Man (1976) — a notion the film’s directors had already heavily promoted in their press tour of the film (Huver).

The film is thus doubly coded as “political” by way of its various evocations — narrative, thematic, aesthetic, extratextual — of the 1970s conspiracy genre: most obviously, in its paranoid plot concerning state corruption, but also in the adoption of Cold War motifs (the titular “Winter Soldier” is a former Soviet assassin), the casting of Robert Redford (famed for his leading roles in Three Days of the Condor and All the President's Men) as Pierce, and the prominence of various architectural symbols of American political power and conspiracy — the film begins with Rogers jogging past various famous Washington landmarks including the Jefferson Memorial, the Washington Monument, and the Capitol building; S.H.I.E.L.D.’s fictional headquarters is situated on Theodore Roosevelt Island, allowing for Pierce’s office to overlook the Lincoln Memorial and stand in front of the Watergate hotel complex (fig. iv).[iii]

The Winter Soldier’s evocation of the conspiracy thriller recalls Fredric Jameson’s famous analysis of the genre in The Geopolitical Aesthetic, which is perhaps his most enthusiastic application of the principles sketched in “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture.” In the book’s first part, “Totality as Conspiracy,” Jameson considers observations from urban theorist Kevin Lynch’s The Image of the City alongside Althusser’s definition of ideology to conceive of “cognitive mapping” as a kind of ideological critique.[iv] Looking to the conspiratorial films of the 1970s and ’80s, Jameson sees unconscious attempts to achieve “self-consciousness about the social totality” under conditions that frustrate our ability to do so (Geopolitical Aesthetic 2). Films like The Parallax View and Videodrome (1983) are thus read as reflections of such a cognitive mapping, attempting to make sense of our place in the global system through their negotiation of the individual, as represented by the civilian-cum-detective protagonist, and the (absent) collective, as represented by the conspiracy. The desire to map the conspiracy becomes precisely the kind of utopian longing, however repressed, that constitutes the possibility of ideological critique.

While this utopian component of the conspiracy narrative is certainly present in The Winter Soldier, it exists in a decidedly more ambivalent form than those films analysed by Jameson. We can demonstrate this by looking to a scene in which Captain America and Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) trace an encrypted flash drive to a secret S.H.I.E.L.D. bunker in New Jersey. Here, they discover a 1970s-era supercomputer containing the consciousness of Hydra scientist Armin Zola, preserved in the form of an artificial intelligence. Zola reveals, in a lengthy piece of beyond-the-grave exposition, the extent of Hydra’s infiltration of S.H.I.E.L.D., and their villainous vision for Project Insight:

For seventy years Hydra has been secretly feeding crisis, reaping war. And when history did not cooperate, history was changed. Hydra created a world so chaotic that humanity is finally ready to sacrifice its freedom to gain its security. Once the purification process is complete, Hydra’s new world order will arise.

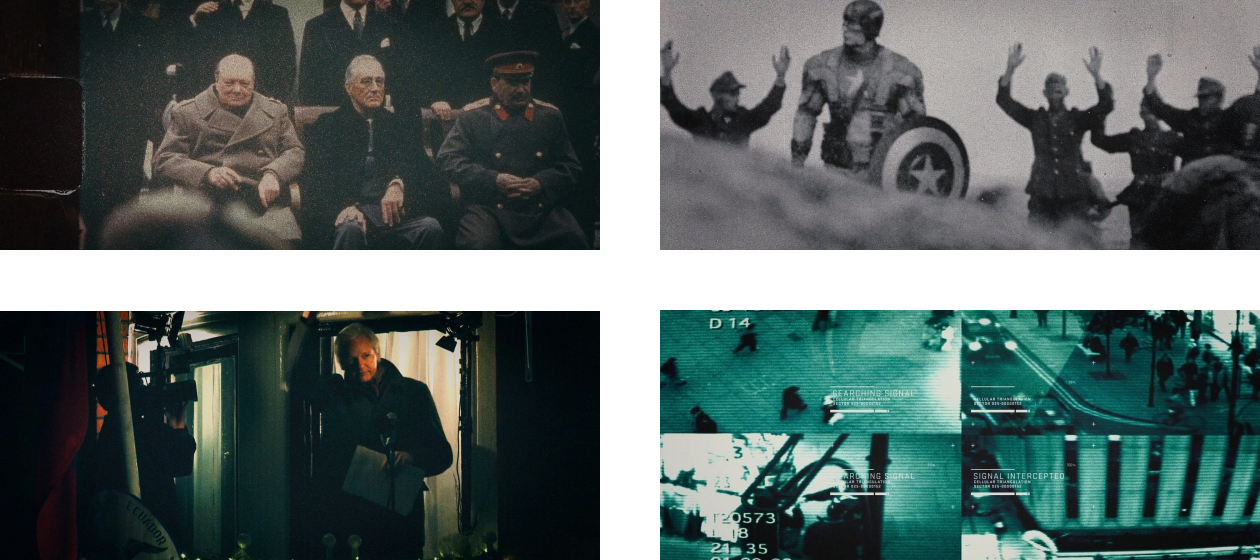

Accompanying the speech is a montage, making use of fast cutting between still and moving images, which seems to be mixing the grainy diegetic footage Rogers is watching on the analogue monitor in front of him with crisp, digital (and thus presumably extradiegetic) images offered to the film viewer. What the viewer sees is a dizzying array of political iconography: real-world historical images of Churchill, Wilson and Stalin at Yalta, Nazi book-burning, the First Palestinian Intifada, the Iranian Revolution, and the 1991 U.S. invasion of Iraq; fictional images of Captain America, the Winter Soldier, and Hydra operatives; and generic images of soldiers at war, aerial bombings, surveillance cameras, redacted documents, space satellites, and so on (fig. v).

On one hand, Zola’s revelations represent the unveiling of a conspiracy that seems to reflect, as in Jameson’s reading, an attempt to map the totality of things — we come to understand that the“conspiracy” the protagonists are chasing is nothing less than the system itself. The montage alludes generally to the U.S. destabilisation of the Middle East, as well as more specific incidents that call into question the benevolent image America projects of itself.[v] In referencing the artificial creation of perpetual crisis to create populations willing to sacrifice personal liberties, Zola’s speech also alludes to the US’ pursuit of what Naomi Klein has described as the “shock doctrine.” And broadly, at least “[a]t the surface level of allegory,” Ryan Vu points out, “the film daringly associates NSA surveillance and the US drone warfare programme with incipient fascism” (127).

At the literal level of the narrative, however, things become muddied. The images shown to the viewer occur in such rapid succession as to register almost subliminally; the sequence recalls, perhaps not unintentionally, the famous “brainwashing” montage in The Parallax View. But do they actually mean anything? A glimpsed shot, for example, of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, famous for publishing evidence of US military war crimes, is included in this montage. Are we to understand that Assange is a Hydra agent?

It is telling that the film mediates its political commentary via an homage to an earlier era of conspiracy narrative; the self-consciously dated image of the “future” in the form of the 1970s supercomputer lends, Vu notes, a “kitsch historicism” to the scene (127). The Winter Soldier’s pilfering of various aesthetic styles of the past recall Jameson’s comments on postmodernism (a term roughly synonymous in his work with the manifestation of late capitalism in culture) and its penchant for depoliticised pastiche. The political commentary in The Winter Soldier is designed to be recognised as genre convention first, politics second. In fact, we could say that the film’s appeal real-world politics is trumped by the conventions of the conspiracy thriller, which in turn is trumped by the conventions of the superhero blockbuster. Jameson notes the irony and cynicism that permeates The Parallax View and other contemporaneous conspiracy films — the anxiousness with which they insist their scumbag New-Hollywood protagonists must not be misread as heroes. As a Disney-owned teaching machine, the MCU cannot afford such moral ambiguities. At no point in the film is Captain America’s status as a symbol of American exceptionalism and absolute good questioned.[vi]

For Brinker, this scene and others demonstrate the superficiality of the MCU’s engagement with politics, which has more to do with the evocation of generic political themes than their substance — what they “say” — which is kept deliberately vague so as to ensure mass appeal. While Brinker’s general argument certainly holds weight in its observation of the superficial and even contradictory ends to which the commodified category of “politics” is deployed here, it perhaps overstates the degree to which the preferred meaning of the text is left open to interpretation. In fact, as in the films looked at in the previous chapter, there is a careful management of how America, and especially its military and defence, is portrayed. Upon closer inspection, the film’s identification of the US government and military-industrial complex with a covert and brutal quashing of civil liberties — which might constitute the genuinely “subversive” quality Lambie ascribes to the film — is neatly sidestepped by its insistence that the literal 1940s-era National Socialist Party has been pulling the strings. A parallel might be drawn with the discursive trend of neoliberal politicians portraying American wrongdoings as un-American.[vii]

The Winter Soldier’s conspiracy narrative can, then, ultimately be read as pseudo-critique of American state power, pushing a “bad-apples” framing to an absurd extreme. In typical neoliberal fashion, government cannot be trusted to supervise itself — it is in need of a strong-man individual to intermittently intervene and put things right.[viii] The legitimacy, however, of a system sustained by a deliberate strategy of “shock therapy,” used to justify mass surveillance and military might, is left unquestioned. Surveillance, in particular, is once again portrayed as unacceptable in the wrong hands (this time, the hands of cartoonish fascists bent on world domination) but its regular deployment by “heroes” (the “actual” American military and its superhero stand-ins) goes unexamined, allowing for Far From Home, released five years after The Winter Soldier, to feature a casually thrown-out plot point involving Peter Parker gaining “access to the entire Stark global security network, including multiple defence satellites, as well as back doors to all major telecommunication networks.” The entire system is exposed as corrupt, but the system itself survives into future films.

[i] Though the character was created in the same year as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence, creator Stan Lee has maintained that this was a coincidence.

[ii] A plot point across multiple MCU productions is the existence of a “super soldier serum,” a chemical solution used by the US military to enhance the body and mind of soldiers.

[iii] Even the presence of specific “easter eggs” reinforce this point. For example, the viewer learns that Zola died in 1972, the same year as the Watergate scandal.

[iv] In Lynch’s book, the alienated modern city engenders a situation in which people are no longer able to make sense of their place in the urban totality; nevertheless, geographical landmarks make it possible for residents to orient themselves, and thus form mental images of the city as a whole. In Jameson’s view, cultural texts perform a similar role in allowing us to orientate ourselves in what he had previously described as the “bewildering new world space of late multinational capital” (Postmodernism6).

[v] For example, a flashed headline reads “GERMAN SCIENTISTS RECRUITED BY US,” which refers in the world of the film to S.H.I.E.L.D.’s enlistment of Zola, but also to the real-world Operation Paperclip, a secret US intelligence program which saw more than 1,600 Nazi scientists brought to the US for government employment between 1945 and 1959 (see Jacobsen).

[vi] In comparison, the films studied by Jameson tend to end with their protagonists dead, suffering a mental breakdown, or at the very least finding their confidence in American institutions irreparably damaged.

[vii] This can be seen, for example, in presidential comments on allegations of torture at Guantánamo Bay. In 2006, Bush claimed that “[t]he United States does not torture. It's against our laws, and it's against our values.” And in the lead up to his own election in 2007, Obama stated that it was time for America “to show that we are not a country that … runs prisons which lock people away without ever telling them why they are there or what they are charged with” (Daily Dish). According to a leaked 2004 Red Cross report, this was exactly what was happening at Guantánamo (Lewis). Despite repeated insistences of its imminent closure from Obama and Biden, the detention camp remains operational at the time of writing.

[viii] The point is made explicit at the film’s end, when Black Widow, faced with imprisonment for acting against the US government in order to expose Hydra’s plan, tells a hearing “You’re not going to put any of us in prison. You know why? […] Because you need us.”