The Wonderful World of Jacques Demy

Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg opens with the following lines of dialogue: “Is it finished?” asks a man entering a garage. “Yes,” replies a mechanic, emerging from the hood of a car, “the engine still knocks when it's cold, but that's normal.” “Thank you.” “Thank you.”

Hardly ground-breaking stuff; only there's a catch — those lines, as with all dialogue in the film, are sung. More a cinematic operetta than a traditional musical, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg heightens even the most mundane chat with melodramatic song. This is the world of French director Jacques Demy, in which every moment holds the potential for profound joy — or misery.

Though Demy has found renewed interest in recent years — largely due to the restorations of his films overseen by Agnès Varda (herself currently receiving a wave of long-overdue appreciation) and for their whopping influence on Damien Chazelle’s films Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009) and La La Land (2016) — many of his films remain frustratingly difficult to even see in the UK.

Jacques Demy was born in 1931 in Pontchâteau, a commune on the west coast of France, and as a child showed a passion for performance and spectacle. At the age of four he built his own puppet theatre, and at nine he was making animations by painting directly on to strips of film. As an older cinephile teen, Demy met director Christian-Jaque, who was so impressed by Demy’s DIY filmmaking efforts that he helped secured him a place at film school in Paris.

In the latter part of the 1950s Demy produced a series of short films, including a documentary about the local clogmaker of his childhood, Le sabotier du Val de Loire (1955), and an adaptation of a Jean Cocteau play, Le bel indifférent (1957). In 1961, he released his debut feature film. Initially, Demy had planned to make it as an extravagant widescreen colour musical, but with a minuscule budget he was forced to shoot in black-and-white and cut back to only a few songs.

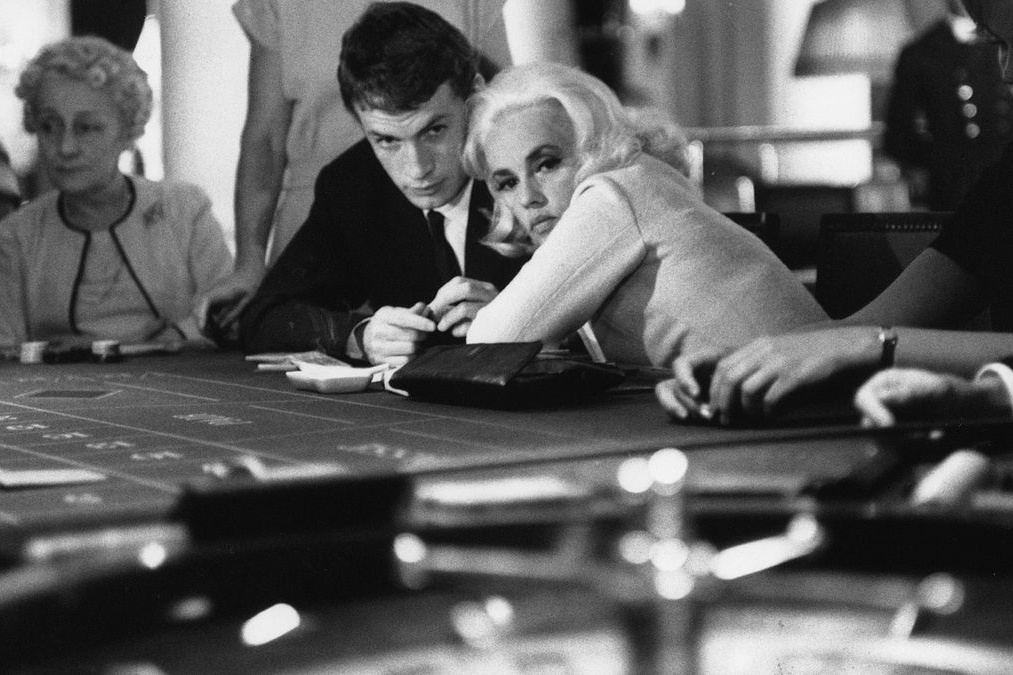

The resulting film, Lola (1961), is nevertheless a wonderful tale of first loves and missed chances centred on a cabaret singer (Anouk Aimée). Skilfully blending the casual cool of the French New Wave with Demy’s romanticism, the film garnered a fair amount of critical attention. Still not enough, however, to allow Demy to make his dream musical. Demy’s follow-up film was Bay of Angels (La baie des anges, 1963), a pessimistic character study about a gambling addict played by Jeanne Moreau.

In 1962, Demy married the director Agnès Varda. Though the filmmaking power couple never worked together, Varda would release two films about him after his death: Jacquot de Nantes (1991), a fictionalised recounting of his childhood, and the documentary The World of Jacques Demy (1995).

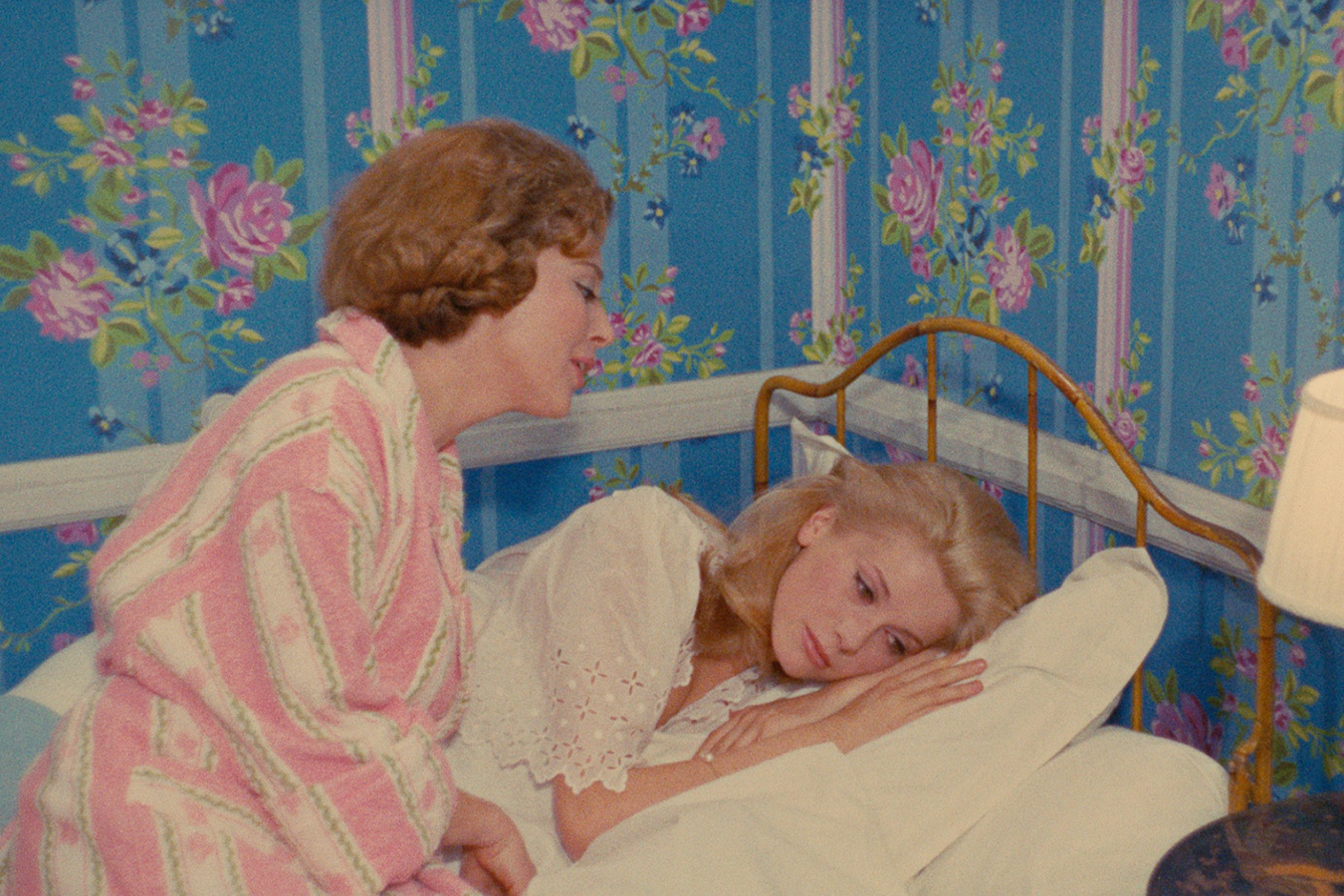

With funding finally secured for a musical, Jacques Demy directed what many consider his masterpiece, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Les parapluies de Cherbourg, 1964). Set to an emotive score by regular collaborator Michel Legrand and entirely sung, the film tells the story of young lovers Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve), whose romance is tested when Guy is drafted to serve in the Algerian War. Despite the non-stop singing and vibrant colour scheme (15,000 francs of the 120,000-franc budget were spent on wallpaper!), it is, in many ways, the antithesis to your run-of-the-mill cheery Hollywood musical. Demy made no secret of his intentions for the movie: “I want to make people cry.”

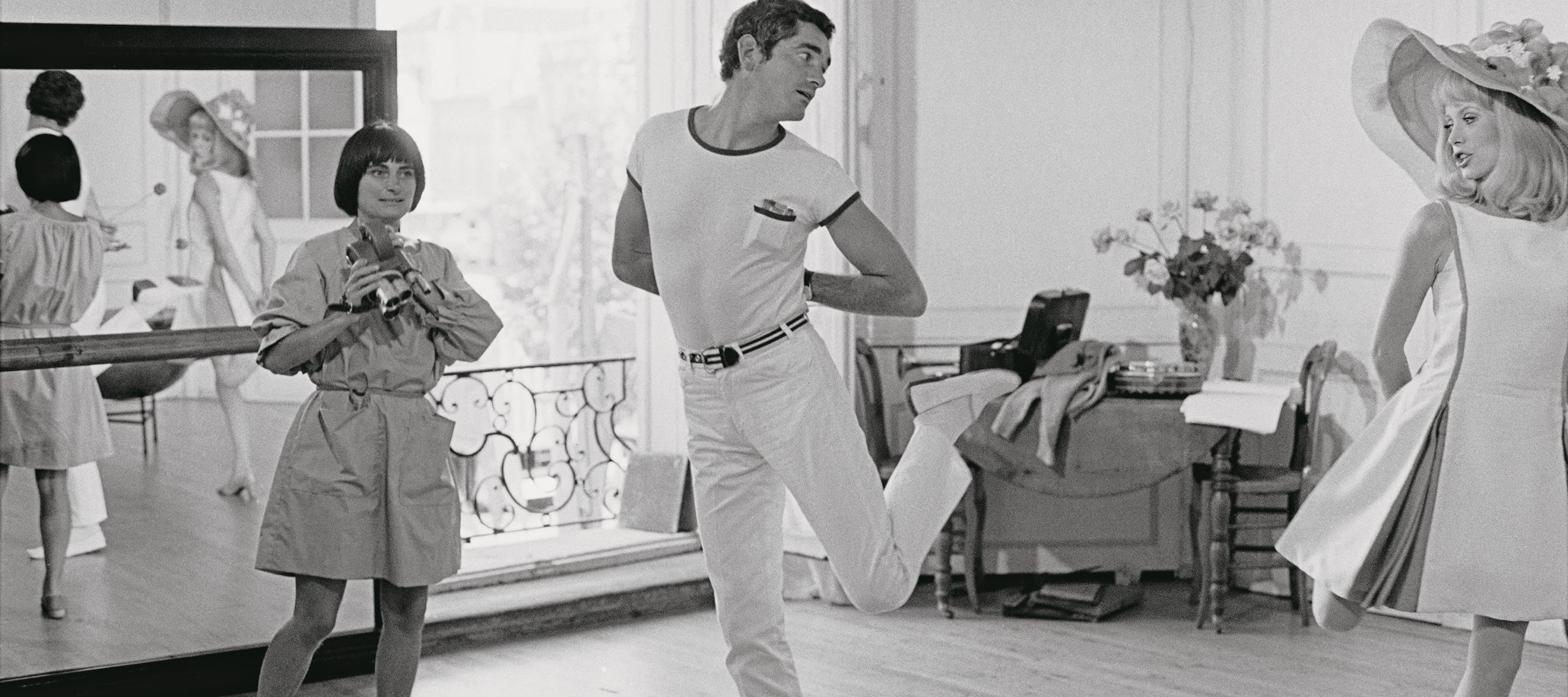

Umbrellas was an international hit, winning the Palme d'Or at Cannes and receiving five Oscar nominations. Its success allowed for the production of an even more extravagant musical collaboration with Legrand, The Young Girls of Rochefort (Les demoiselles de Rochefort, 1967). Again starring Catherine Deneuve, this time alongside her sister Françoise Dorléac, Jacques Perrin and Gene Kelly (yes, really!), the film is a Shakespearean farce of coincidence, fate and missed connections set over a weekend of festivities in the town of Rochefort. An antidote to the heartbreak of Cherbourg, Demy’s candy-coloured Rochefort is — on the surface, at least — pure joy.

The success of the two musicals landed Demy a contract with Columbia Pictures, and in 1968 Demy and Varda went to Hollywood to shoot the drama Model Shop (1969). The film picks up the story of Lola, the protagonist of Demy’s first film, now working in Los Angeles. Model Shop was a critical and commercial failure (Demy would later refer to it as “Model Flop”) and the following year Demy was back in France.

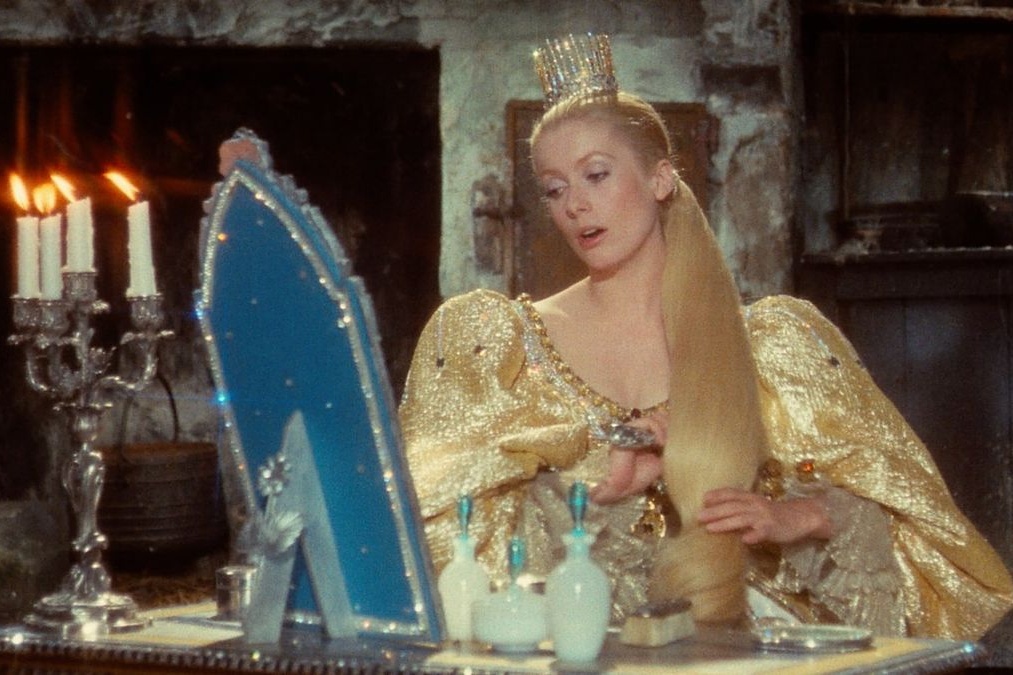

Donkey Skin (Peau d’âne, 1970), literalised the fairy-tale quality of his earlier films in the most bonkers way imaginable. The kitschy musical centres on a young princess (Deneuve again) who flees the kingdom wearing the skin of a magic donkey in order to escape from her father the King (Jean Marais), who is set on marrying her. Featuring a throne shaped like a giant fluffy cat and a fairy godmother who travels by helicopter, it makes for a viewing experience not unlike Cinderella on psychedelics.

Though Donkey Skin was his greatest commercial success, Demy struggled to find critical favour during the ’70s. The Pied Piper (1972), a much more grounded fairy tale, was a clunky attempt at British filmmaking, while his feminist comedy A Slightly Pregnant Man (L’Événément le plus important depuis que l’homme a marché sur la lune, 1973) was seen as somewhat disposable (and no doubt its ludicrously long French title scared off some viewers). Lady Oscar (1978), an English-language period piece based on a Japanese manga — about a girl raised as a boy to guard Marie Antoinette — didn’t even get a proper release in Demy’s native France.

Hoping to repeat the magic of Umbrellas, Demy returned to the operetta-musical form with A Room in Town (Une Chambre en ville, 1982), a ’50s-set melodrama about another doomed romance, this time against the backdrop of a workers' strike in Nantes. He received the Prix Méliès for the film, as well as the Grand Prix des Arts et Lettres — a lifetime achievement award. Still, it was not enough to rejuvenate his reputation abroad, and Demy’s final trio of films — Parking (1985), La Table tournante (1988) and Three Places for the 26th (Trois places pour le 26, 1988) — remain relatively obscure.

Demy died in 1990 at the age of 59 “of a brain hemorrhage brought on by leukemia,” or so the New York Times reported. In reality, it had been complications related to AIDS that had tragically claimed the director’s life so soon, but the stigma surrounding the disease meant that the truth did not become widely known until the release of Varda’s documentary The Beaches of Agnès (2008). To this day, there remains a frustrating coyness — both in critical work and from Demy’s widow — about the director’s bisexuality.

In many ways, Jacques Demy’s story is the classic tale of an artist held back by their own triumphs — he could never quite recreate the success of his early musicals, and critics were increasingly unkind to his work as his career progressed. As his New Wave contemporaries become increasingly politicised — with Jean-Luc Godard founding the Marxist Dziga Vertov Group, and Varda herself turning to more explicitly feminist work — one of the common criticisms of Demy’s oeuvre was that it was too fanciful, too detached from reality. Critics targeted Demy’s dedication to kaleidoscopic colour schemes, his emphasis on technique, and his love of artifice, fairy tales and sing-songs, and asked: is that it?

No, that was never it. Demy’s work was always political, dealing with social issues as disparate as the domestic damage of war (Algeria in Umbrellas, Vietnam in Model Shop), social unrest and class exploitation (A Room in Town, The Pied Piper), and incest (Donkey Skin and Three Places for the 26th). He interrogated questions of gender (Lola, The Young Girls of Rochefort) and blurred them (The Pregnant Man, Lady Oscar), and since his death his films have been re-evaluated through the lens of queer studies — with the recurring theme of forbidden or impossible love now readable as queer coding from a more repressive time.

For all the sunny seaside settings, the wonderfully garish wallpaper, and the glorious high-camp musical numbers, a sense of tragedy and darkness underlines Demy’s films. Viewers might come away from The Young Girls of Rochefort swooning at Demy’s colourful paradise, but they’d better not forget the subplot about a jilted lover turned axe murderer with an obsession for a beautiful ex-dancer — hinting at the dangers of romantic idealisation. Or, more obviously, there’s the bittersweet ending to The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, where our protagonists, frozen in cinematic time, are left pondering what could have been.

Jacques Demy’s greatest skill as a filmmaker was finding magic in the mundane, and then undercutting that magic with melancholy. His technicolour dreams tip-toe the line between the ridiculous and the sublime — and whichever you feel wins out, it’s surely impossible not be moved by his films.