Growing Up With Ghibli

Like a lot of people my age, two animation studios defined much of my childhood movie-watching experiences. First came the films of Walt Disney Animation Studios — classics like The Aristocatsand The Jungle Book, alongside Disney Renaissance films including Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King. Then — a bit later, when we’d made the switch from VHS to DVD — came the films of Studio Ghibli, especially those of director Hayao Miyazaki: My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle and the like. I adored both sets of films for their stunning hand-drawn animation. Looking back, however, I can see that these films were also what scholar Henry Giroux, in his book on Disney, calls “teaching machines” — and that the studios that produced them were imparting very different messages.

Children’s films function as a kind of passive-but-pleasurable learning space, adopting at least as much cultural authority for teaching specific values as the more traditional sites of education. It’s for this reason that, although adult audiences seem especially willing to suspend critical judgement on children’s films (even more so on animated children’s films) there’s no getting around the fact that they’re inescapably political. Popular culture is ideology, and in the case of Disney it’s ideology that takes pains to present itself as anything but — as ‘just’ entertainment, innocent and entirely unrelated to the real world it provides an escape from. At least, this was the view taken by Walt Disney himself, who famously once quipped, “We just make the pictures, and let the professors tell us what they mean.”

The problem for Walt is that much of what the professors have had to say about Disney since at least the ’60s has been fairly scathing of its conservative politics. Most early criticism of Disney focused on gender stereotyping in the princess films — problems that weren’t exactly fixed with Disney’s resurgence in popularity in the late ’80s with The Little Mermaid. The racial stereotyping found in older films like Dumbo and Lady and the Tramp survived into Aladdin and The Lion King, and the sugar-coated depiction of colonialism in Pocahontas is fairly representative of Disney’s dodgy ahistoricism. Add to this an uncritical obsession with wealth and undemocratic forms of power, and it starts to look like there might be a problem with the kind of world Disney wants to teach children about. “As capitalism, it is a work of genius; as culture, it is mostly a horror,” wrote Disney biographer Richard Schickel, for whom Disneyfication was a serious concern. “When fascism comes to America,” he claimed, “it will be wearing mouse ears.”

I’m not sure I’d go that far. I still have a real fondness for a lot of those films, and to be fair to Disney we’ve seen small steps towards more progressive worldviews in more recent Disney outings like Frozen and The Princess and the Frog. Nevertheless, as a child I came away from Studio Ghibli’s oeuvre feeling like I’d been presented with a very different look at the world to that promoted by the Disney canon. Though their narratives also focus on fairy-tale-like journeys of self-discovery, Ghibli — and Miyazaki's films in particular — repeatedly subvert the simplistic Disney-esque messages of “be yourself”, “follow your dreams,” and “find a man and settle down” in favor of alternative imaginings of identity, community, embodiment, love and family, not to mention strong anti-military and environmental themes.

Take, for example, Howl’s Moving Castle, in which the protagonist Sophie is transformed by a witch into an old woman, finding refuge in a magical moving castle belonging to the wizard Howl, who she falls in love with. On the surface, Howl’s Moving Castle looks like Miyazaki’s most straightforward fairy tale, and certainly his most romantic. But though the film shares with Beauty and the Beast an interest in the transformative power of love — Sophie’s love for Howl is the only thing able to break the curse on both her and him — its focus is less on conventional heterosexual union than it is on the alternative family of misfits that’s formed over the course of the film, and on the pointlessness of the war Howl refuses to be drawn into.

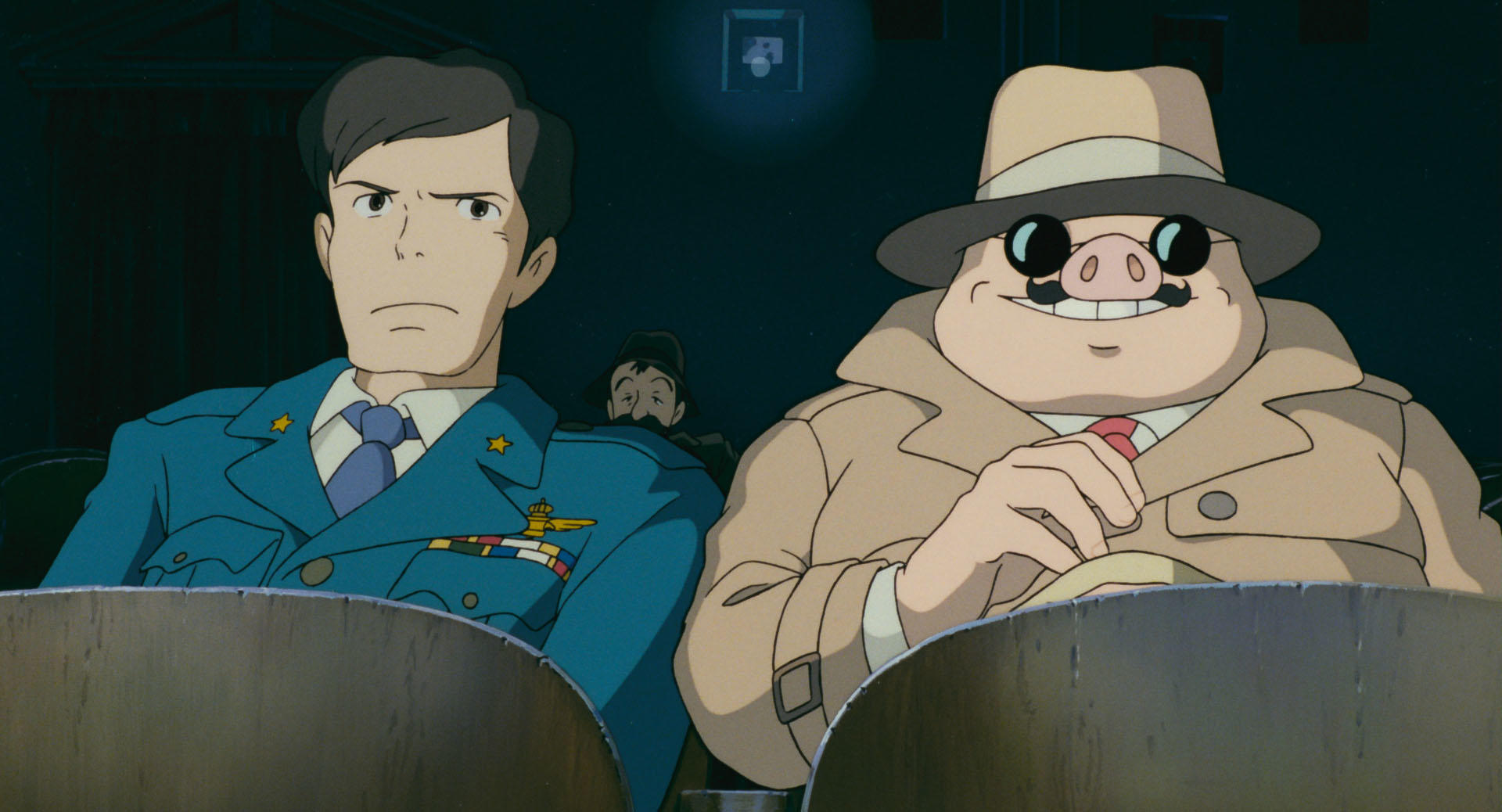

As Sophie’s curse implies, metamorphosis is a key theme taken up across Ghibli’s output, albeit with a different emphasis to that found in Disney. In Porco Rosso, the protagonist — a pilot transformed into an anthropomorphic pig — is hardly concerned with returning to his human form. Unlike Disney’s Beast, Porco recognizes the appeal of his supposedly grotesque alterity; set against its backdrop of the rise of Italian fascism, the film insinuates being a pig might not be such a bad choice in a world of human cruelty. (“I’d rather be a pig than a fascist,” Porco puts it) In fact, a beguiling flashback scene suggests that Porco’s real curse isn’t his porcine appearance, but rather survivor’s guilt deriving from a traumatic experience in the First World War. Relatively heavy stuff for a children’s comedy-adventure about flying sea pirates

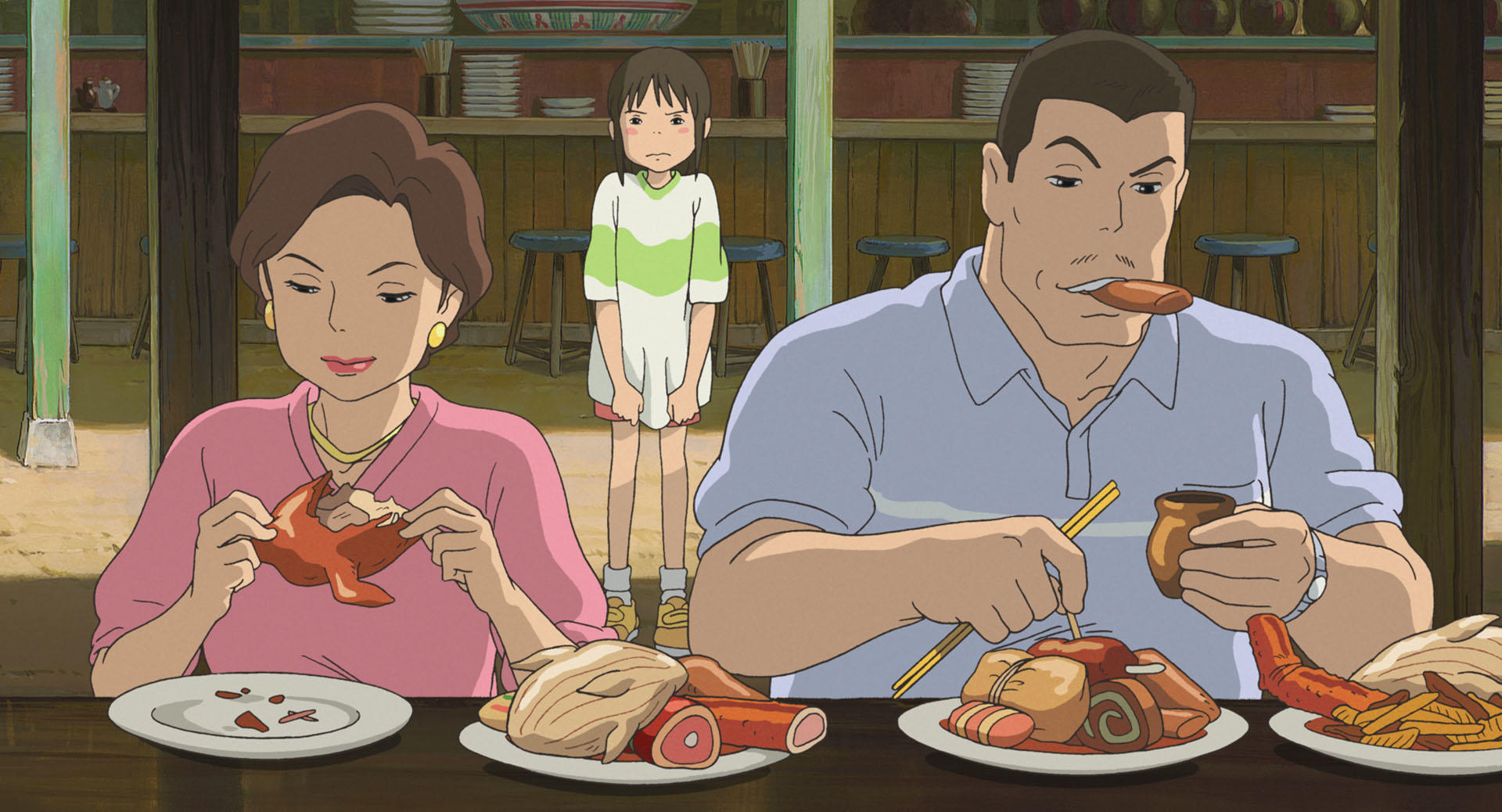

In Spirited Away, too, it is Chihiro’s parents that are famously transformed into pigs — although here the emphasis is on their greed. The theme of society falling prey to excess recurs throughout Miyazaki’s filmography, and it’s here that his strong environmental concerns tie in. Princess Mononoke, a Kurosawa-scale epic set in a fantasy version of fourteenth-century Japan, sees protagonist Ashitaka caught in a struggle between the animal gods of a forest and the humans of Irontown who are greedily devouring its resources in a bid for economic and military supremacy. On the surface, the villain of the story would appear to be Lady Eboshi, the often ruthless leader of Irontown. We learn, however, that Eboshi has also used her position to help various stigmatized sections of society, from lepers to sex workers, and internally Irontown is presented as fairly appealing. Rather than rejecting modernization and proposing a total return to nature and the past, the film urges us to find the balance between the human and natural worlds. For a ten-year-old, this was incredibly compelling stuff — and Princess Mononoke is still my favorite movie.

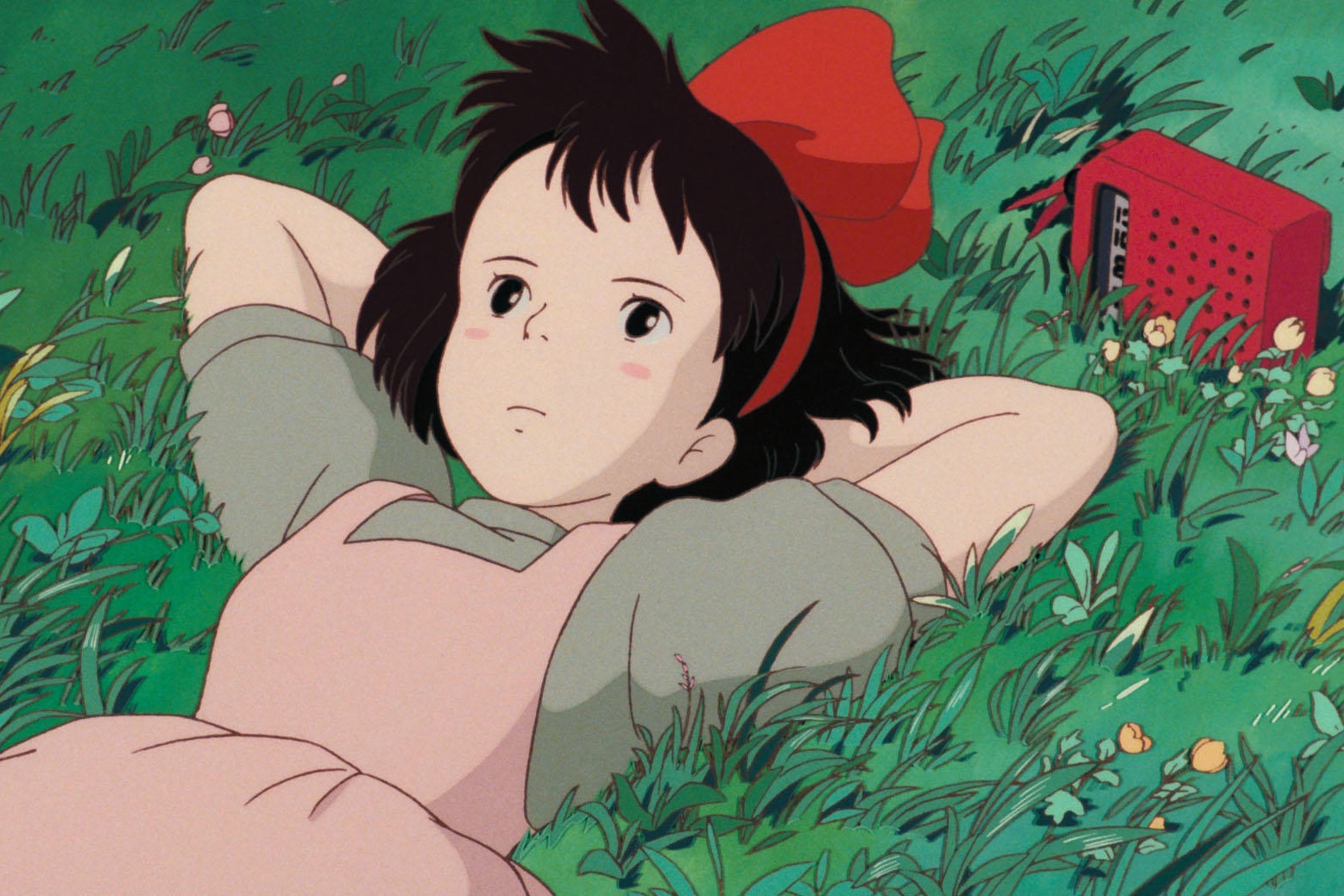

Disney has its fair share of iconic villains, but none come close to the complexity of Lady Eboshi. For all its colorful animation, Disney’s depiction of morality remains strictly black and white. Miyazaki, on the other hand, relishes in the morally grey, often choosing to redeem villains against our expectations. Films like My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service or Whisper of the Heart take a different (but no less radical) approach and do away with villains entirely. The fear that hangs over the witch Kiki, for example, isn’t some kind of magical adversary, but rather loneliness, self-doubt, and the realization that artistic pursuit comes at a cost. Kiki, unsure of how to connect to people and the city she has arrived in, has to work her way out of a depressive slump that causes her to lose her powers. The metaphor is a simple one, but the emotional truth of Kiki’s narrative feels positively revolutionary for a kid’s film.

In the end, I think it all boils down to imagination. The entertainment value of Disney’s aesthetically gorgeous animated classics is hard to dismiss, but it’s rare that they have the imagination to dream beyond the existing hegemonic social order. Miyazaki’s films are just as striking on an audio-visual level, yet also convey — to even their youngest viewers — the urgent need to imagine different, better worlds. A desire for deeper kindness and understanding is at the heart of Miyazaki’s cinema, and as Ghibli increasingly enters the Western mainstream, I often find myself reflecting on whether these films have the potential to radically transform the value systems of the children who watch and adore them.