Interview: Will Anderson

Edinburgh-based animator Will Anderson won the 2013 BAFTA Award for Best Short Animation for The Making of Longbird, his graduate film for the Edinburgh College of Art. He has since been nominated in 2015 for Monkey Love Experiments and again in 2018 for his latest film Have Heart, which won Best Short Film at this year’s British Animation Awards. Have Heart sketches the day-to-day life of Duck, an animated duck who has a job as a looping GIF. Facing pressure from his boss at work and feeling somewhat isolated in his relationship, Duck’s repetitive lifestyle causes him to have an existential crisis. What results is one of the most original, witty and heart-warming short films of recent years. In this interview, Will Anderson talks about Have Heart, social media, meta-cinema and how he ‘kind of went into film by accident’.

I saw Have Heart at London Film Festival and I really liked it a lot. I came into it having read the tagline ‘A looping GIF has an existential crisis’, so I thought it might be funny, even thought provoking. But I wasn’t expecting how moving it was. Was this something that you’d always planned?

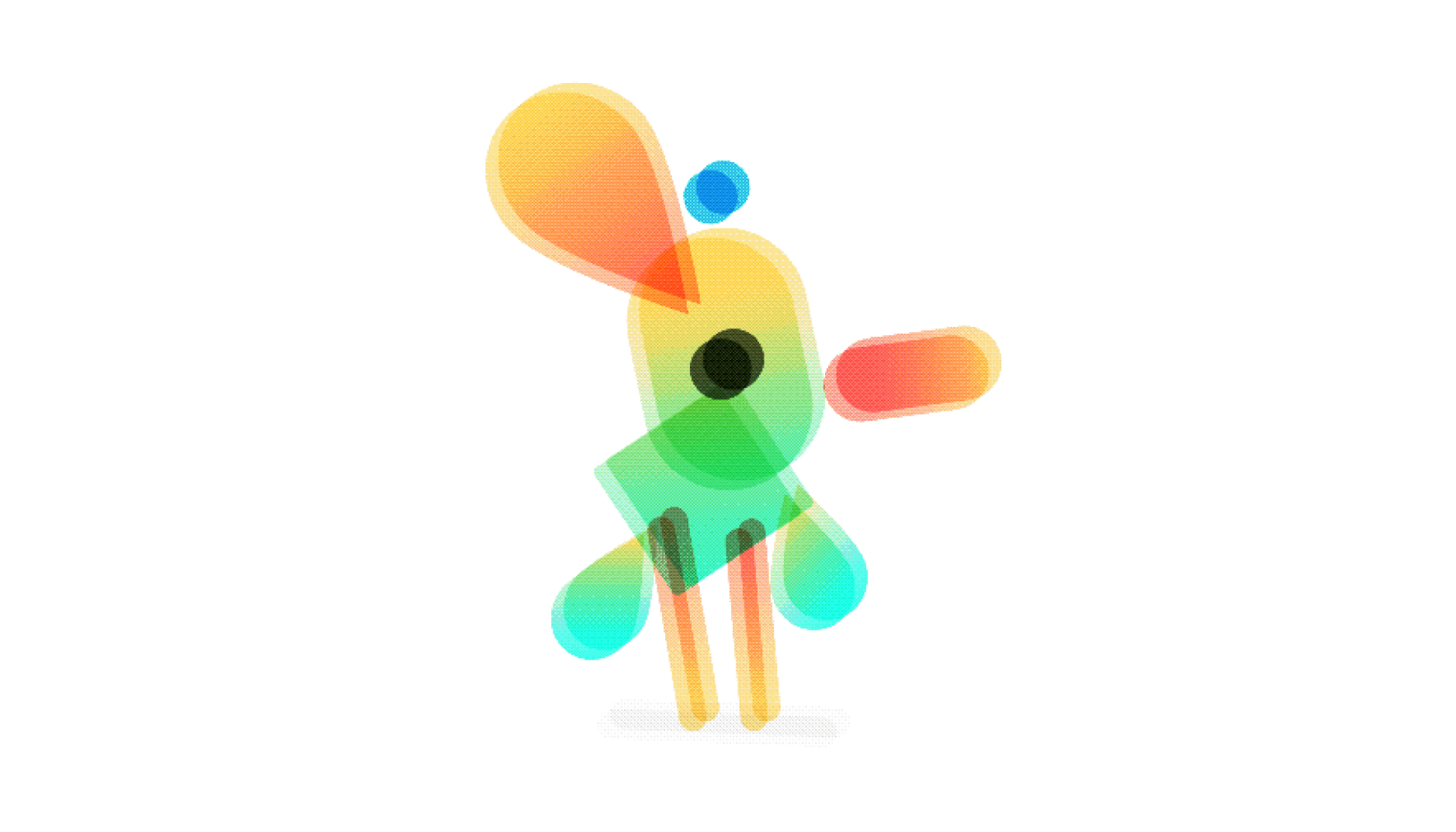

Well, ‘planned’. The film wasn’t planned in the first instance because the first thing was this looping GIF that the film is about. It’s this duck – this collection of shapes – that is jumping up and trying to fly and then crashing down to earth and falling to bits. It’s a perfect loop, it keeps going back and forth and back and forth. I wasn’t really thinking about making a film, necessarily, I was just being an animator. It’s part of my job, and part of my interest in design is to make things and just play around with shapes. And that’s essentially what that loop was. Then I started looking at it, and it made me feel kind of sad and hopeful at the same time because – kinda like the glass-half-full-half-empty thing –you could look at as pathetic, he’s trying endlessly to fly and falling to bits, or you could see it as his refusal to give up. After watching that loop I think I decided there’s something kinda sad and possibly powerful if I do it right, if I tell a story about what life’s like for that little GIF.

It works as a metaphor for repetitive life, just going round and round, and I guess that, in quite an unpretentious way, Duck’s very relatable.

Yeah, everyone feels like they’re stuck in their job sometimes, or stuck in their relationship, or feeling a bit trapped and isolated, particularly online. Everyone’s sort of part of it now, and it’s easy to feel like we’re, you know, kind of stuck in a rut and kind of anxious there. I’m quite anxious, I feel quite anxious a lot of the time, so making a film about that, it made sense.

Every time he loops, he gets these little hearts coming off him, which kind of resemble the ‘likes’ you get on Twitter or Facebook…

Yeah, and they are not that many! I quite like that – this isn’t like a global meme, it’s actually just pretty pathetic, which makes it more human as well.

So you were thinking about social media when you made this?

Yeah, definitely. I suppose just intuitively making it, putting it in a square, I kind of imagined it on a social media stream. Then I put it on Twitter or something, and that’s when I started looking at it, thinking about it a little bit more. And then it became a comment on social media; our identity online, what that means, and if it’s important… or if its maybe not that important.

Given that the GIF duck is presumably living inside the internet in this film, it’s quite funny that probably a lot of people are going to watch this on their laptop. Do you think it’s particularly suited to online viewing?

It’s funny that, I’m not sure. It’s been playing at film festivals for the last year and a half or something. As a filmmaker who’s making shorts, that’s the route it’s quite common to go down – send it to film festivals, get a bit of interest, and get people in theatres seeing it. Weirdly, I originally thought that, after I completed it, this might work online, because it’s about online. But I’m not that sure yet. We’ll find out, but I think because it’s so out of place in like a cinema, because it looks like something you’d see online – it’s got bright colours and it’s quite sparse as well, design-wise – I think it kinda stands out in a cinema which has surprised me. It’s twelve minutes and I think it’s quite a challenging watch for someone on their laptop, you know what I mean. And it’s a slow-ish film. I saw it a bit like a theatre thing: we follow this mundane going back and forth to work with this character, going home and having his dinner. It’s not like high-octane action or anything like that. But I think that it surprised me that it was a bit more for cinema.

I think there’s a different kind of resonance when Duck tries to break out of the screen. When you see that on the cinema screen that’s obviously pretty startling. But if you’re watching it on your laptop, in a sense it’s more immediate because it’s trying to break off your own personal screen. In The Making of Longbird, a film you won a BAFTA for, the character also comes out of that internet video frame and starts looking at the comments. Do you think you’re particularly interested in meta-film?

Definitely, definitely! I’m glad you asked that.

Where does that come from?

I did animation at Edinburgh College of Art, and part of that is film studies. I think I was looking at films, when I was making Longbird, that were kind of quite metaphysical. Films like F for Fake by Orson Welles, where he rehashes an old film and then it becomes this other film, that was pretty fascinating to me. Films that reference that they’re films are things that I love, like the work of Charlie Kaufman, he kind of does it a little bit. And I suppose that animation is such a constructed thing, it’s an illusion, so you’re trying to trick people into it not being that, to suspend themselves. When you say, ‘oh by the way, this is an animated film, it’s not real’ and you’re being playful with it, I really like the tension that that creates. It’s kind of funny. Longbird’s like that, it’s kind of funny. That’s what I thought about this GIF as well, it’s kind of ridiculous that we’re gonna zoom in on this guy’s life and find out what he eats for breakfast and what he does with himself. I think the absurdity of it – like, why would anyone make that? – actually drives me to make some things, which is kind of a strange thing to say. But I think it’s true, because I do like laughing, I like things that are funny. I also like things that are thoughtful, that challenge you a little bit, even if that’s visually and that’s being playful with visuals, I enjoy making films like that.

You mentioned the influence of that certain type of film – did you come into animation from a film studies background or from a more ‘arts’ background?

Well, I kind of went into film by accident, because I went straight from school to the art school studying animation, not realising that you had to make a film in the last year. Obviously when I started the course I leaned quite quickly, but I would never have said that I was a filmmaker. I’ve always been interested in drawing and I always keep a sketch book, and I’m always writing down my ideas and stuff like that. So, yeah, more of an art background, though not a professional one, just an interest. And then I just, I don’t know, felt animation was the hardest thing I could try to do, because you never stop learning it. It’s just movement and that movement says something about a character and that character is part of a story and that story can say an infinite number of things to the world. It felt like a really exciting and challenging thing. I still have absolutely no idea how I’m doing at it, but I find it exciting.

Have Heart is entirely digital animation. Is that something you’ve always done, or is this a new progression?

This is the first fully animated short film that I’ve made. I’ve made lots of animation things, various sketches and things, but in terms of what I consider like ‘oh that’s one of my short films’ this is the first time I made it entirely animated. We – and I’m referring to ‘we’ because I often work with this guy Ainslie Henderson, we write together a lot – normally work with live action. We often talk about how there should always be a really good reason for something to be animated. I’m not really that interested in making a film that’s animated that could otherwise be live action – just do it live action, I think. The first film Longbird is about struggling with your creativity and it’s about resurrecting an old animated character and he’s made out of paper, so it’s like, okay, that character’s made out of paper, I’m me, and I’m trying to animate it, so it’s a live action film, essentially. We did another one called Monkey Love Experiments which was the point of view of a monkey in a cage, so it made sense to make that animated, but everything else was live action. With this one, it’s about social media, so it makes sense for it to be animated. If you’re talking about social media it’s from the point of view of a GIF, it can’t really be anything else but animated, in my head anyway.

There’s the bit where you zoom in on the duck’s beaks and they’re translucent, so they overlap and make a circle. I thought that was a very clever use of that internet GIF form, looking at it closely.

I think when I started I thought it was gonna be quite an experimental film, and I am in to some experimental film. And then, as I was making it, it actually felt quite logical – he goes to work and comes back, he has his dinner, he looks at the stars, he loses his job then he tries to do something else, then he gets sucked out the window of his house and tries to make this break for it, that’s essentially the story. It’s not that experimental, it’s actually quite a straightforward story. But I am interested visually in testing a little bit, so that’s why I liked extreme close-ups and pixels sort of breaking apart. I suppose I’m interested in things that are playful with the form, and that’s when you’re talking about meta-films, that interests me.

There’s bits that have that glitchy feel, and you also get that in the sound design. How much did you contribute to that?

The sound’s done by a guy called Keith Duncan and the music’s Atsi, and they’ve done most of the films we’ve done. We worked for a long time on what the sound of this should be. Because the visuals are sparse and very digital-looking, it’s like the sound really had to carry it and match it. Keith originally put the sound to that opening loop, which helped add more weight to it, when he did that – spent a long time on just a little, a loop that lasts like four seconds – we realised this was gonna be a really intense sound experiment as well as a visual one. Every moment, every step has a sound, which does come across as being quite abrasive at times, for it is a 12-minute film that has no human dialogue. But I quite like that, and I think that it’s deliberate, that it has this abrasive edge to it and that it tests your patience a little bit, particularly when it’s talking about the worth of likes and love online and what that actually means.

You say it’s got that abrasive quality to the sound, I think you get that in the images as well. When Duck gets more existential, things go wrong visually.

Oh yeah it becomes almost a strobing effect, it’s almost like falling apart. Which is kind of what he’s been doing anyway in his job, he’s been falling apart.

It contrasts really nicely with the emptier moments, the sparseness of the images and sound

I just hope that that space doesn’t make people switch off. And again, in the cinema they’re trapped in there, they’re not going anywhere.

I think it’s the contrast that makes it work because at points there’s a lot to take in and then you get these breathing moments that are actually very emotionally affecting. One thing I was curious about is that a lot of your characters are ducks or birds – is that something you’ve always liked drawing or is there a deeper reason…

I think it started with Longbird, because Longbird became a symbol of struggling with my creativity. Out of that, we were gonna make a TV show with this world of birds, so I made this full world of birds and then me and Ainslie do these sketches that we like making and put them on the internet and all that, so it kind of made sense to use birds. My mum’s kind of afraid of birds, I think she watched Hitchcock’s The Birds when she was younger and she can’t walk down the street – if there’s a pigeon there she’ll cross the road and walk on the other side. So maybe it’s like a … I don’t know … a subconscious thing.

Moving on from Have Heart, you’re working on a feature film for the Scottish Documentary Institute. Can you tell us a bit about that?

So I’ve been writing and directing a hybrid animated doc feature film – there’s a lot of words there. It’s basically about a family coming to terms with the mother of the family getting cancer, and how we talk about it, how difficult it can be to talk about things, how you process dealing with your mum’s mortality. There’s an animated character who kind of embodies the cancer and kind of speaks for it. It’s kind of about speaking about cancer. But it’s quite playful! We’ve shot documentary footage and, as there’s an animated character, there’s a story we’ve written alongside the documentary. So it kind of weaves in and out of fact and fiction, which like I mentioned before really interests me. We know there’s an animated character talking to you there, but it’s no less real than the feelings that the family has about the fear of death and the fear of losing the people they love. If they’re not communicating properly, animation felt like this slightly abstract thing that would help convey really complex emotions. They probably couldn’t do without animation. It’s year four now of development, we’re just getting the finances together and we’re on track for finishing by the end of the year. So hopefully it will be at some festivals next year.

Finally, what advice would you give to young, aspiring filmmakers, particularly animators?

When I was making stuff, I didn’t think my ideas were that valuable, or that interesting, and I think I’ve been a bit surprised over the last few years that your ideas are really valuable, because they’re yours. You should be as confident as you can be with your work because people will listen, and try to be honest, because people really respond to it I think. I was genuinely shocked when I started playing in festivals and people were laughing, it was such a strange experience. You just have to put yourself out there really, and be honest. Believe in your ideas, because they’re important. I’d say that’s the quote.